Empathy and mindfulness: can you have too much?

A Limbus lecture and discussion at Dartington on 3 February 2018 led me to these questions.

The lecturer, Dr Guy Millon, began by contrasting empathy as understood in Western psychology and in Buddhism. A counselling psychologist who practises meditation, he lives out both approaches. They can support each other: for example meditative practice (widely presented these days as mindfulness) enhanced the quality of attention Millon was able to offer his clients.

But what of the antithesis between these approaches? Psychology attends to building up a healthy ego, whereas Buddhism embraces ‘no self’. This tension motivated Millon to conduct interviews with 14 mental health professionals who also practised mindfulness. His focal question was, ‘What role does empathy play in your practice?’

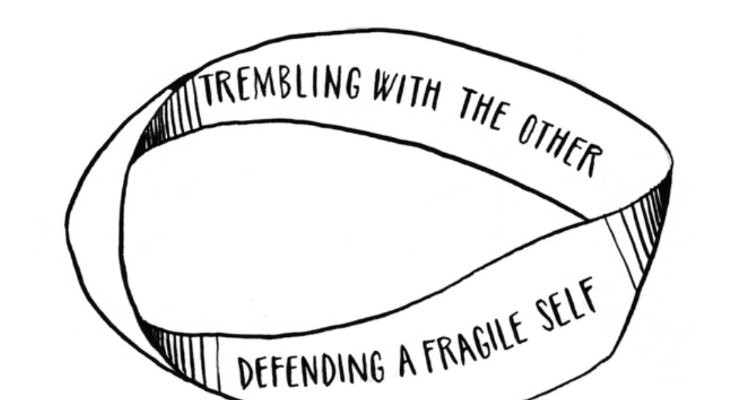

When Guy’s thesis appears in article form it will make for rich reading; being part of his audience was a treat. Making sense of the experience of his subjects, as well as Eastern and Western ideas, led him to give us all to take away a Möbius strip ‒ a simple collar of paper given a half-twist before being joined to itself. On the collar is written ‘defending a fragile self’ and, seemingly on the other side, ‘trembling with the other’ (a Buddhist definition of empathy).

Except that a Möbius strip has only one side: trace a pencil onwards from one set of words without interruption or lifting and you come to the second set. The invitation is to think a healthy self and no self not as opposites but as paradox.

Put another way, Millon pointed to two co-existent moves in the therapeutic dance: holding the other at a distance to avoid being overwhelmed, and experiencing separateness dissolve like an illusion. The moves are not sequential: it’s not ‘at one time this’ and ‘at another time the opposite’. Instead the apparent opposites are always present and always interdependent.

Where Millon locates empathy within this paradox is fascinating. At first glance being skilled at reading feelings evidently belongs to ‘trembling with the other’. Concrete instances of close connection do so belong; however, speaking about empathy as an abstract ideal ‒ an unsullied good of which the therapist considers himself to be a skilled producer ‒ was often part of defending the therapist’s fragile self. ‘Bigging up’ empathy means selves are separate: it pushes them apart, creating a space for skilled professional intervention. For me, this was a rich new thought. To over-simplify – the simplification is mine, not Millon’s – it is possible to have ‘too much’ empathy.

Ahead of the lecture I read the new book ‘Mindfulness for Coaches: An Experiential Guide’ by Michael Chaskalson and Mark McMordie (Routledge 2018; McMordie is a colleague of mine at Coachmatch). After introducing mindfulness, the authors show in detail how it relates to many different coaching models. They go deeper: there are chapters on empathy and psychotherapy. The book is a seminal text, admirably written and full of knowledge, wisdom and generous acceptance. But for me, Millon’s lecture prompted a question.

From the UK All-Party Parliamentary Report on Mindfulness, the book quotes words from Jon Kabat-Zinn:

Awareness in its purest form, or mindfulness, thus has the potential to add value … to living life fully and wisely and … to making wiser and healthier … choices … going beyond the limitations of our presently understood models of who we are as human beings. (pp. 164-5, ellipses in the original).

While always careful in their language, the authors evoke a world in which mindfulness takes practice and discipline, but we can never have too much of it. I pause, considering how Millon unpacked a similar idealisation of skill and result in relation to empathy. It is helpful to be shown the potential of mindfulness. It is also helpful to be reminded why it cannot be an unsullied good. We can have too much mindfulness.

Limbus was established 20 years ago to create events of interest to psychotherapists and counsellors, and others within the helping professions or interested in the human condition. Dr Guy Millon is a counselling psychologist at the West of England Gender Identity Clinic and in private practice. Dr Douglas Board is head of Coachmatch Career Management, a senior visiting fellow at Cass Business School and a satiric novelist.

Don't we have to understand first what 'self' means in the two traditions? I think we are talking about two (at least partially) different concepts. Thanks for the thought-provoking piece, Douglas.