Habits can be broken, but not forgotten

Maybe you chew your fingernails when you’re nervous. Or scarf down chocolate when you’re sad. Or take home a stray kitty whenever you see one, until the SPCA has to come rescue them all and have you arrested for being a hoarder.

Chances are, you have a few habits you wish you didn’t have, and quite possibly you’ve tried (and tried and tried) to break them. Scientists are learning why you may have failed (and failed and failed). In fact, they now know that once you have a habit, you can never really unlearn it.

“Once it’s there, it’s there,” says Ann Graybiel, the Walter A. Rosenblith professor of neuroscience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass. “It really will never leave.”

Great.

Still, no need to panic.

The fact is, even though you can never simply delete habits from your brain and be rid of them once and for all, you can stop indulging in them if you really, really want to -- and scientists have been learning more about that, as well. But be warned: Breaking up with a habit is ha-a-a-rd to do.

“There’s an expenditure of energy involved in changing behavior,” says Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse in Bethesda, Md. “That’s where motivation comes in.”

Habits are learned behaviors -- ones you’ve become trained to do almost without thinking. When you’re first learning to drive a stick-shift car, it may seem beyond the power of any mortal to coordinate such complex maneuvers: pushing in the clutch, shifting gears, letting out the clutch, stepping on the gas. You stall at lights. You roll backward down a hill or two. But you start to get the hang of it, and before you know it, you’re shifting automatically (so to speak).

Shifting has become a habit -- something you’ve done so often that you hardly have to think about it any more.

“In habit learning, neural patterns get drilled into the brain,” Graybiel says. “This is good for survival.”

And, for the most part, it’s good for simply getting through the day. All the little routine things you do by habit -- from putting on your shoes to combing your hair to picking up after your dog -- leave your mind free to think and plan and solve problems and contemplate the important issues of our time, like, say, how did computer geek Steve Wozniak ever survive so long on “Dancing With the Stars”?

Goal in sight

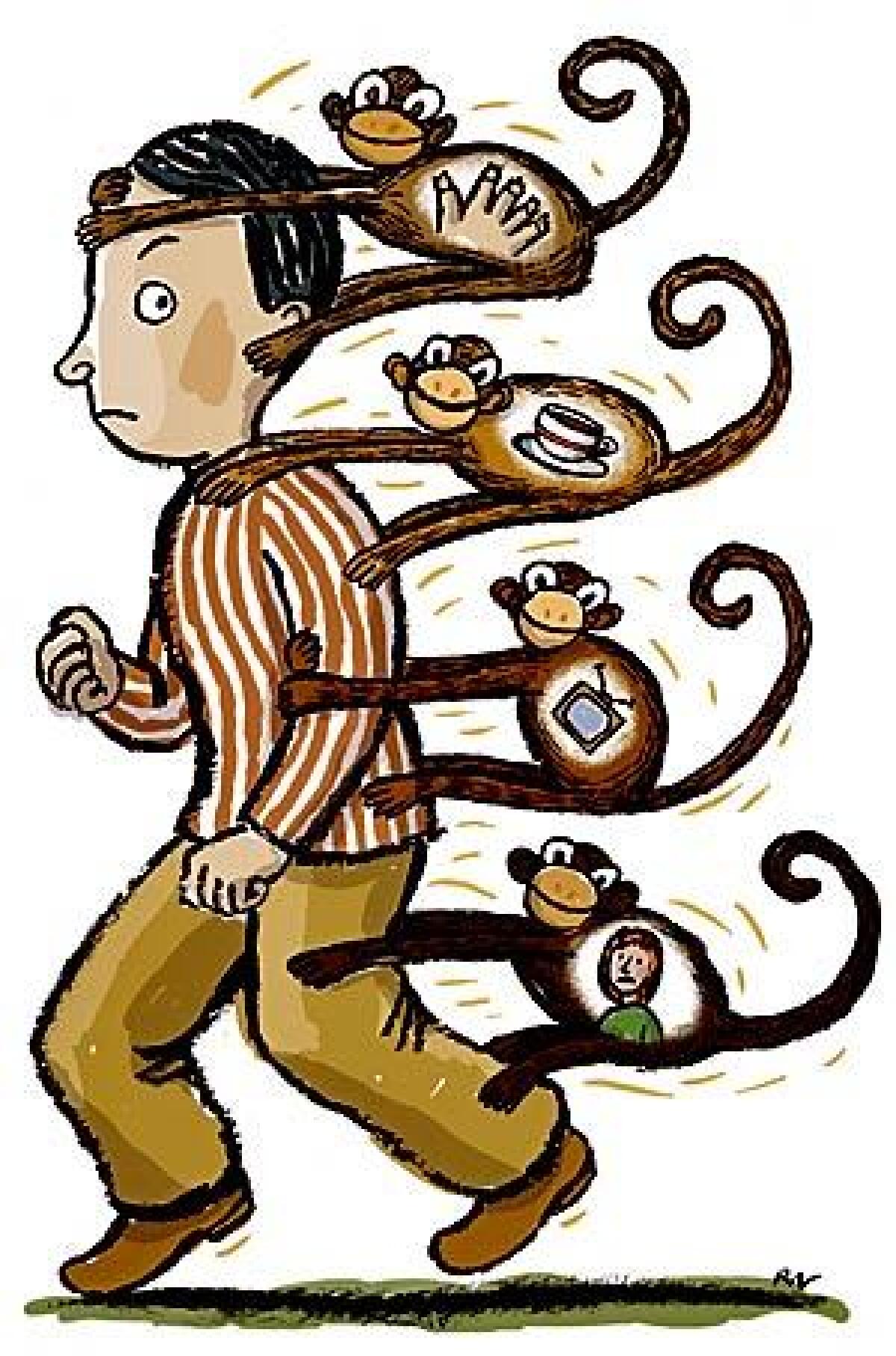

But then there are those other habits, the kind that can throw big monkey wrenches into your life -- overeating, over-shopping, biting your nails, not biting your tongue, biting off more than you can chew and then procrastinating.

Habits you’d like to disown.

Scientists theorize that in acquiring a habit, be it good, bad or innocuous, you typically start out with “goal-directed behavior,” meaning you perform a certain action in a certain situation because you expect to reach a certain goal. But if you repeat this same action in this same situation over and over, you get to the point where you take a particular action in a particular situation simply because you’re in that situation. Your goal has dropped out of the equation.

There’s evidence to back up this theory. In one Duke University study, currently under review for publication, researchers gave students popcorn to eat while watching movie trailers. Sometimes the popcorn was fresh, popped an hour before the movies started. Sometimes it was stale, popped seven days before.

All the students had a preference for the fresh popcorn. And the researchers found that people who didn’t make a habit of eating popcorn at the movies showed goal-directed behavior (the goal was eating something tasty): They ate much more popcorn when it tasted good than when it didn’t, “which is what you would probably expect everyone to do,” says Wendy Wood, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke and a study co-author.

But you would be wrong. People who had a popcorn-movies habit seemed to eat the popcorn simply because they were at the movies: They ate just as much regardless of whether it tasted good or, as Wood termed it, “disgusting.”

Human beings are hard to study, so it’s lucky for scientists in this field that rats, like people, can be creatures of habit.

In studies, researchers have trained rats to press a lever to get the reward of a food pellet and then started putting food poisoning on the pellet to make the rats feel ill. Some rats then stopped pressing the lever, or at least pressed it much less often. Researchers inferred that these rats had been showing goal-directed behavior -- they’d been pressing the lever to get the food, and, presumably, were feeling shortchanged by the sickening pellet.

But other rats kept pressing the lever as much as ever. Researchers inferred that the sickening pellet didn’t faze these rats because pressing the lever had become a hard habit to break.

Another, 2005 study with rats, published in Nature, found that old habits never die. They don’t even fade away, exactly. Researchers trained rats to run a maze when they were given cues to tell them whether a food reward (chocolate) was at the right or left arm of the maze. In fact, they “over-trained” the rats till the behavior became a habit. Then they broke the habit (by reducing or completely cutting off the reward). And finally, they restored the reward and trained the rats to run the maze again.

The rats’ accuracy and speed in running the maze increased rapidly during training, then fell sharply while the habit was being broken. Then it jumped back in almost no time during re-training.

During all of this, the researchers recorded nerve cell activity in the striatum, a brain region important for goal-directed behavior as well as learning habits. In the initial training, the striatum was active during the entire maze run. But once the rats were in the habit of running the maze, just being placed in the maze was all it took to make them run it. Not much was going on in their striatums; they were running on automatic pilot.

The findings also show that once you have a habit, you may break it -- but you don’t forget it, says Graybiel, senior author of the study. “The minute you put the reward back, it’s back.”

Evolution at work

Why do we do things if they’re bad for us?

We can blame it partly on how we’re made. “Over the course of evolution, a present good was worth two in the bush,” says James Gross, psychology professor at Stanford University. That’s because early on, life tended to be short.

The upshot? Our brains are built to overvalue the rewards we can get right away and undervalue those we might only receive later. Similarly, we tend to avoid any small unpleasantness we’d have to face now even if we know it may mean bigger difficulties down the road.

Over the ages, humans have learned to think about, and plan for, the future. It’s still not easy for us, though. “If you’re not motivated,” Volkow says, “there’s a real danger of giving in to immediate gratification.”

Another part of the problem is that habits set when we live one way become counterproductive when our lifestyle changes.

Consider, for instance, swimming phenom Michael Phelps, who became almost as famous last summer for his mega-meal-eating habit as for his gold-medal-winning habit, and in whose honor the term “Phelpsian” was coined to mean “amazing.”

Taking in 12,000 calories a day, as Phelps has been reported to do, would be a mistake of Phelpsian proportions for, say, 99.9999% of the world’s population. But it’s apparently a pretty good habit for Phelps.

Right now. Twenty years down the road, though, it’s not likely that Phelps will be swimming so fast, so often, so calorie-consumingly. If he can’t rein in his habit then -- and very often, top-flight athletes cannot -- he’ll reach Phelpsian proportions himself.

“Don’t damn habits,” says Bernard Balleine, psychology professor and associate director for research at the Brain Research Institute at UCLA. “Just damn habits that are uncontrolled.”

Habits need not be all-powerful, irresistible forces that run our lives. You can usually suppress one if it’s going to get you into trouble, Balleine says.

Peter Gollwitzer, professor of psychology at New York University in New York City and at the University of Konstanz in Germany, is optimistic about the prospect of breaking bad habits. “You can do it,” he says, “by a simple act of will . . . You can do it with your mind.”

Graybiel is more cautious. “There isn’t necessarily a very strong connection,” she says, “between the thinking brain and the habit brain.”