This talk was presented at the Council of Basic Writing Pre-Conference Workshop, The Conference on College Composition and Communication, Houston, TX, 6 April 2016.

Introduction

In this presentation, I will lay out a provisional plan I am developing for integrating disability studies principles into the daily practice of a small basic writing program at Western Washington University, a mid-sized state university in northwestern Washington State. Taking to heart the fact that this is a workshop session, I have brought you today a true work in progress. I hope you will be able to give me feedback, and that my experiments will motivate you to try some of the techniques I will discuss today.

The central question I’m trying to explore here is how can a disability-studies approach motivate me to develop novel practices in my basic writing classrooms. When I say disability-studies approach, I am referring to a philosophy that moves beyond the idea that disability is a problem to be solved; rather, disability studies honors and affirms disabled peoples’ unique perspectives and capacities. In this context, disability experience is seen as a source of insight, and disability identity is recognized as a vital cultural identity centered on values of radical acceptance of difference, mutual support, and collective action.

For the purposes of my presentation today, I am focusing on two types of disability with which I have personal experience—learning disabilities and psychosocial disabilities. For at least three decades, Basic Writing instructors have recognized the need to better understand the unique needs of students with learning disabilities, including dyslexia and other language-processing differences. In large part, our concern with these students has grown apace with the rapid expansion in the student population itself, especially at two-year colleges. In the last decade, we have also seen increased attention being paid to the growing population of students with a wide range of psychosocial disabilities. Here I borrow Margaret Price’s term to indicate a wide range of disabilities that include psychiatric conditions, emotional impairments, and developmental conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorders and ADHD (Price 2013).

I don’t want to focus today on the difficulties these students face in current-traditional basic writing instruction. There is plenty to say on this topic, and for those interested in it, I’d recommend especially Patricia Dunn’s book Learning Re-Abled: The Learning Disability Controversy in Composition Studies and Margaret Price’s Mad At School: Rhetorics of Metal Disability and Academic Life. (Incidentally, session A.01 on Thursday is focused on a the legacy of Dunn’s book twenty years after its publication.) You should also check out the excellent annotated bibliography maintained on disabilityrhetoric.com, which includes a range of articles addressing specific impairments and particular issues in traditional writing instruction.

Instead, I am trying to imagine ways that we can design basic writing curriculum that put the skills and sensitivities of people with learning disabilities and psychosocial disabilities right at the center of day-to-day practice. To illustrate what I mean, I will talk you through my plans for next fall, when I will take over as lead instructor of the small basic writing program at Western Washington University. I will describe some pedagogical experiments I am planning to build into my courses, and give some indication of how I hope to study the effectiveness of these experiments.

Basic Writing at Western Washington

Western Washington has a small, low-pressure basic writing program, especially compared to the kinds of programs in place at my graduate institution where I trained, the City University of New York (CUNY). Western has an average student body of fifteen thousand undergraduate students, with an incoming class of about 3,000 every year. These students are required to take and pass a first year writing course in order to satisfy their general education requirements. Students who enter the university with low scores on the SAT writing exam or in their high school English courses are flagged during registration for placement in the basic writing course, English 90. This course is voluntary—so students are able to opt in to the course if they feel they’d benefit from the extra writing instruction. It is graded on a pass/fail basis, and earns students three credits toward graduation.

The population served in these BW classes tend to be either first generation college students, who are usually white, or international students. It is structured as an intensive, immersive introduction to both writing and college life generally, with classes every day, Monday through Friday, and class sizes capped at 20 students.

To me, this basic writing setup offers interesting possibilities for experimentation. Students opt in, and there is no high-stakes exam structure to prepare for, which allows us room to focus on writing process and gradual development. Additionally, I see useful opportunities to link tailor the course to Western’s rapidly growing population of students with disabilities. In the past fifteen years, the number of students registered with the disability services office has grown from approximately 250 to over 1000 campus-wide. The vast majority of these students, according to the current program director, either have learning disabilities or psychosocial disabilities, or both. I hope that by tailoring the course curriculum to the needs and talents of these populations, I will be able to grow the impact of the basic writing program, and also promote more accessible pedagogy upward throughout the writing program.

I will briefly describe some curricular experiments I am planning to implement, and then conclude with some considerations about the logistics of this pedagogical research.

Learning Disability and Writing About Writing Processes

The typical impairment model for learning disability (LD) defines in terms of diminished capacities compared to the typical learner. The generally accepted model characterizes LD as a cluster of neurologically based information-processing difficulties—for example, slowness in the ability to process visual information, diminished working memory, or other weaknesses in the individual cognitive capacities required to do the work of learning. Obviously, many of these skills are important to success in a heavily reading-and-writing based college class.

Counter to this impairment model, we can also describe LD in terms of benefit or increased capacity. LD literature is full of references to increased abilities in oral/auditory information processing. Many people with LD are attentive listeners and can process audio texts without difficulty. Likewise people with LD are often confident talkers, able to articulate complex ideas without the need for written notes. Indeed, LD has historically been diagnosed by identifying extreme discrepancy between strong oral processing and weak processing of written texts.

LD is also often associated with strengths in abstract visual thinking. Patricia Dunn explored some compelling approaches to incorporating visual thinking into the writing classroom in her book Talking, Sketching, Moving: Multiple Literacies in the Teaching of Writing, for example, having students draw pictures of thesis statements or to express complex ideas in diagrams. As she points out, there is a rich tradition of visual conceptual thinking well honored in the sciences especially. Our field’s narrow focus on linear textual production—on sentences and cohesive paragraphs as the vessels of meaning—overlooks the fact that many students, can best express and understand their ideas when composing in non-linear forms.

Based on these positive understandings, and my own experiences as an LD composer, I am planning to pilot two kind of pedagogical experiments in what I’m calling dyslexic styles of composing. I’ll reiterate, these are not teaching methods designed only for dyslexic and LD students: they are mainstream practices inspired by the typical strengths of this neurodivergent minority.

First, I plan to integrate oral and audio technologies fully into my practice. The most straightforward approach I’m taking is providing downloadable audio files for every piece of class-assigned reading. To do this, I have secured through my new department a professional license of Kurzweil 3000, which is a sophisticated literacy support program designed for students and professionals with LDs. Within a single program, it allows me to scan printed texts, perform optical text recognition, and synthesize mp3 files using a range of natural-sounding voices at a range of speeds, which I can then upload to our class website. I will also include in the syllabus a number of text-to-speech generators that students can install on their web-browsers and mobile devises, which will allow them audio access to our course websites and discussion forum.

My goal here is to offer audio processing as a mainstream option for the entire class, to normalize this typically dyslexic-only practice. I also plan to take advantage of the intensive, five-day class schedule to help students explore dyslexic modes of composing.

At this point, oral dictation software is cheaply available. Indeed, it is built in to most smart phones at no additional cost. Even the gold standard program, Dragon Naturally Speaking, which used to run in the hundreds of dollars, can now be purchased for a reasonable price. These tools allow students to compose written texts using their voices, an approach that offers important benefits to all of us who process our best ideas aloud.

It is time that we more fully explore what these programs can do to help students broaden and personalize their composing processes. I think the same is true of visual mapping tools, including the ubiquitous mind mapping apps like MindMeister. Again, these tools are typically cheap or free, and they offer all students alternative means for generating ideas, growing their texts, and sharing their thoughts with others.

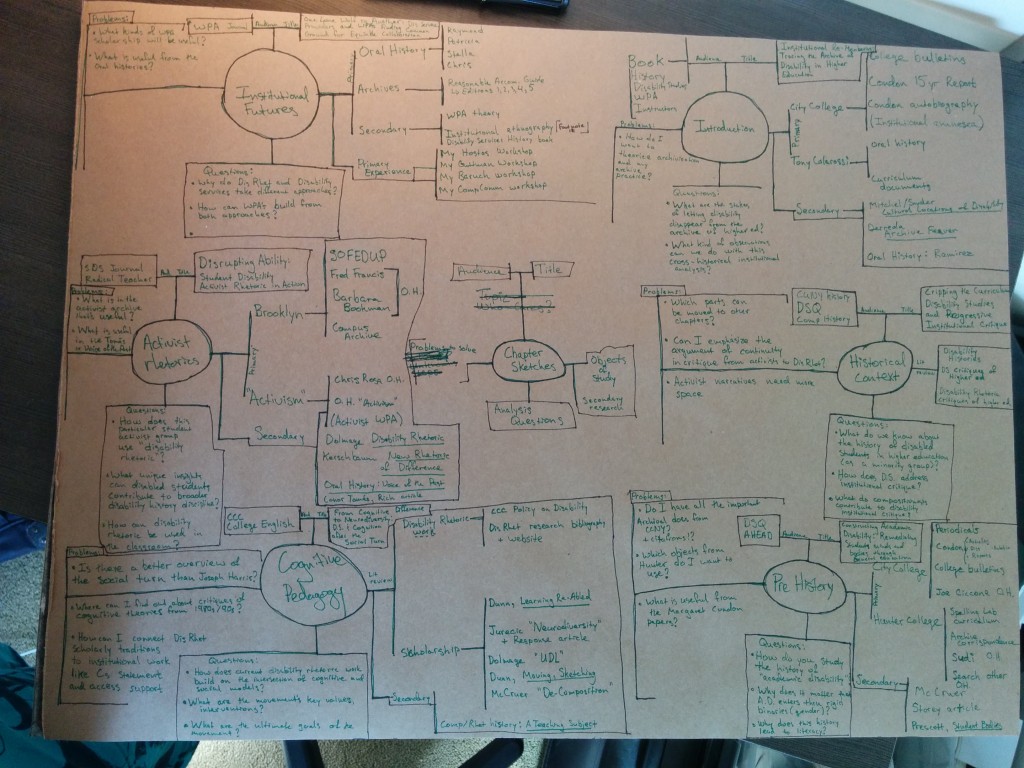

I’ll wrap up with some provocative examples from my own dyslexic composing process. While I have been teaching students to use mind mapping as a revision tool for some years, I am now working on developing formal exercises that can be used with full classrooms of students. Here, for instance, is a mind map I developed to process through the network of secondary sources in each of my dissertation chapters.

Image shows a hand-written mind map. There are six clusters of circles, each with the name of a chapter in the center. A complex web of citation, questions, and bullet points are attached to each chapter node.

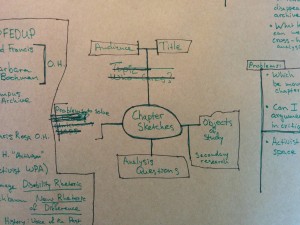

Image shows the key of the mind map. A small circle extends in four spokes. At the top spoke is Title and Audience. Right spoke is object of study and secondary research. Bottom spoke is Analysis questions. Left spoke is Problems to solve.

In the center of the map is a key, which explains the meaning of each section of this node-based map.

I am developing a set of protocols that can guide students through creating such a map, similar in structure to Sondra Perl’s Guidelines for Composing. I hope that by refining this practice with some roomfuls of my basic writing students, especially within broader discussions of diverse writing processes, I will be able to develop a teachable method for incorporating sophisticated abstract visual composing into the mainstream writing curriculum.

Nagging Questions and Next Steps

I have focused here on learning disability and dyslexic modes of composition. However, I also see strong possibilities for incorporating the needs and talents of people with psychosocial disabilities into the curriculum. I’d be happy to talk about this more in the discussion, but I think particularly an attention to collaborative community building in the classroom and a deep focus on the emotional side of writing can help improve writing classes for a wide range of marginalized students.

My goals in these experiments are two-fold. For my work at Western, I hope that I can expand the scope of Basic Writing for the campus, turning it from a small auxiliary program into a vital site of experimentation. I hope as well that these courses can be a site for campus community building, where the growing population of incoming students with disabilities can learn to be academic leaders, and can see a home for themselves in the growing writing program.

Obviously, I also hope that the findings from my experiments will be useful to the field as a whole. I know that it’s hard to picture what a small, low-stakes program like the one I’ll be taking over can offer to institutions with heavy structures of mandatory remediation, ballooning class sizes, and the other difficulties that still characterize basic writing across the nation. I don’t pretend that what I do in my classroom will be universally applicable to others. However, I do think that the relatively sheltered environment of Western’s basic writing program will allow me the room to try out disability-inspired modes of teaching and writing, and thereby develop some novel approaches to accessible instruction methods. I hope you will help me think through this plan further.

Works Cited

Dunn, Patricia A. Learning Re-Abled: The Learning Disability Controversy and Composition Studies. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers, 1995. Print

—–. Talking, Sketching, Moving: Multiple Literacies in the Teaching of Writing. 2001. Print.

Price, Margaret. “Defining Mental Disability” The Disability Studies Reader, 4th Edition. Ed. Lennard J Davis. New York: Routledge, 2013: 292-299.

—–. Mad At School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011.