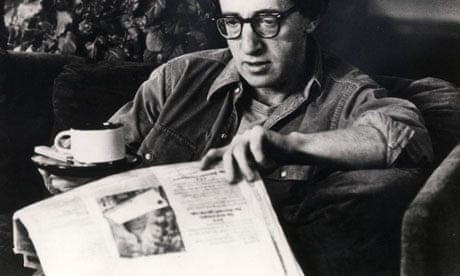

Prone to "constant self-flagellation, anxiety and repressed sexuality" – that was the observation from TV presenter and Nature podcast editor Adam Rutherford after a recent debate on standards in science reporting at the Royal Institution. In a tweet summing up the profession he dubbed science journalists the Woody Allens of the media world.

Well, at the risk of perpetuating that image, here is another bout of self-analysis, but hopefully one with a little data to back it up.

The RI event (set up by the Guardian's Alok Jha and expertly chaired by Dr Alice Bell, who will summarise some of the unanswered questions in an article on Thursday) touched on many of the often-discussed issues that emerge in the debate about journalistic standards in health, environment and science: checking copy with scientists; journalists doing too many stories to be thorough; verification versus stenography; lack of specialist sub-editors etc. If you missed it you can watch it here and here.

I wanted to pick up on a question that produced (for me at least) a surprising degree of dissent in the room. One member of the audience asked: should science specialists read the original research paper when writing their story?

Ananyo Bhattacharya, Nature's online news editor and one of the panellists in the debate, said it was not necessary for journalists to read a research paper they were writing about. He later clarified his thoughts in a response on the Soapbox Science blog by Matt Shipman.

"If the question is 'must a good science journalist read the paper in order to be able to write a great article about the work' then the answer is as I said on Tuesday 'No'. There are too many good science journalists who started off in the humanities (Mark Henderson) – and some who don't have any degrees at all (Tim Radford). So reading an academic research paper cannot be a prerequisite to writing a good, accurate story … So I stick to the answer I gave to that question on the night – no, it's not necessary to read the paper to write a great story on it (and I'll also keep the caveat I added – it's desirable to have read it if possible)."

Just to be clear, we are talking here about standard news stories based on a single journal paper – the science hack's bread and butter. For me, the answer is straightforward. Of course a good science/health/environment journalist should read the paper if possible. It is the record of what the scientists actually did and what the peer reviewers have allowed them to claim (peer review is very far from perfect but it is at least some check on researchers boosting their conclusions).

Without seeing the paper you are at the mercy of press-release hype from overenthusiastic press officers or, worse, from the researchers themselves. Of course science journalists won't have the expertise to spot some flaws, but they can get a sense of whether the methodology is robust – particularly for health-related papers.

In any case, very often the press release does not include all the information you will need for a story, and the paper can contain some hidden gems. Frequently the press release misses the real story.

The tricky question is whether you go ahead and write the story if you can't get hold of the paper. I think a blanket ban would be going too far. Sometimes, it is not possible to get hold of the research paper in the time available.

In many cases, if the research is uncontroversial and fairly straightforward to understand – and especially if the story is short – this may not matter much. But for controversial stories where you need outside comment, there have to be times when a good reporter decides to walk away from the story, even if there is a risk that other less scrupulous media will run it. If the claims have important ramifications or the evidence sounds fishy, then it is not good enough to rewrite the press release.

Since the mood in the RI's famous Faraday lecture theatre was far from unanimous on this point, though, I thought I would ask the nation's science specialist news journalists for their opinions.

I emailed 46 journalists, from national newspapers, newswires, the BBC, ITV and Channel 4, and ex-specialist reporters now freelancing or in PR. I received 24 responses. In my email I did not prompt them with my views. Here's what I asked:

When writing a standard news story based on a paper in a scientific journal how often do you get hold of the paper and read it? always/mostly/sometimes/never

If you think it is important to read the original paper please explain why? How much of it do you typically read?

If you don't read the original paper most or all of the time why not?

Apart from one tabloid specialist reporter, they all replied that they "always" or "mostly" read the paper when writing/broadcasting their stories. Here's how the results break down.

Ex-specialists: Always (0); Mostly (6); Sometimes (0); Total (6)

Broadcast: Always (2); Mostly (3); Sometimes (0); Total (5)

Broadsheet: Always (3); Mostly (3); Sometimes (0); Total (6)

Tabloid: Always (0); Mostly (0); Sometimes (1); Never (0); Total (1)

Mid-market: Always (1); Mostly (2); Sometimes (0); Total (3)

Newswire: Always (1); Mostly (2); Sometimes (0); Total (3)

And there is a lesson here for press officers. One or two of the reporters mentioned the frustration of spending valuable time trying to get hold of the research paper for a story. Why don't all press releases come with the paper attached?

It might sound trivial to get hold of the paper from the researchers direct. After all, most of the time a reporter would want to interview them anyhow. But asking them for the paper before the interview inevitably introduces delay – particularly if the researcher is in a different time zone or if they have a busy day.

Press officers: the clear message is that specialist science journalists need and want to read research papers to do a good job, so please make sure they are easily available online or with your press releases.

I've pasted the responses below from the journalists who got back to me (many thanks to all who took the time to respond). Some were happy to be quoted by name but others gave their comments on condition of anonymity.

A national specialist journalist

"I always read the paper and read about 80 to 90% of it, if not all. Especially looking at method, conclusions, caveats, discussion etc.

"The only exception would be if I couldn't get the paper (Eurekalert is terrible for this, they should force institutions to supply links to the papers in every case) …

"I think it's really important to read the paper because press releases are often wrong, and it's the only way to get the full gist of what researchers are saying. I do feel sorry for non-specialists who have little experience of reading papers though, as many must feel forced to rely on press releases."

A broadsheet specialist

"Always get the paper. Always read abstract intro conclusions, occasionally more. I think it's important so you know what the resarch actually says, not what the press release says. They are often different. It also means you can ask better questions of the scientist."

Sarah Boseley – health editor, Guardian

"I always get the paper and always read all of it …

"I think it's really important because even if the press officer has correctly summarised the meaning, they still may not pull out of it the same angle, interpretation and quotes that you would. Press releases skate over really interesting stuff sometimes in the interests of economy. That's not a criticism. I just think a press release is a guide to what's in the paper (and can offer a very useful interpretation of difficult stuff) but it's way short of the real thing.

"And it doesn't really take that long."

A tabloid specialist journalist

"If I think it is a larger story of page lead length it is certainly worth delving into, but probably two thirds of studies will make much less – simply a few pars only and for that reason there isn't the necessity to be as forensic."

Tim Radford – former science editor, Guardian

"Now and for many years, I have always tried to read the original. For a few paragraphs at least. If only because I felt better talking to the bloke if I had the paper in front of me …

"Chiefly so that I could say to the guy: I've stared at your letter/review/paper and I haven't the foggiest idea what it means: please tell me.

"Sometimes I could almost understand a fraction of it but I still said the same thing. Such a question usually produced interesting and unexpected sentences, anecdotes, asides and revelations; sometimes even completely unexpected stories.

"Also I learned quickly enough that press releases related to original published papers sometimes didn't seem to say quite what the paper seemed to say: and that press releases sometimes didn't make it clear that the research into the astonishing efficacy of garlic pills in the control of migraine/epilepsy/irritable bowel syndrome had been funded by the garlic pill manufacturers' association."

David Shukman – BBC science editor

"Always. It's the final version of the scientists' findings. It's meant to be a calm distillation of their research, and it's been through peer review (far from a faultless process but usually better than nothing).

"The whole thing. I particularly check the sample size and the duration of study and look to see if the authors are from more than one institution and preferably more than one country (I like to think that the more varied the authors, the smaller the risk of any in-house bias).

"Over the years I've seen enough overenthusiastic press releases to know that the quest for publicity and funding can lead press officers to stray beyond the limits of the paper. I don't necessarily criticise them for that but it's another reason to anchor coverage on the paper."

An ex-science specialist on a national newspaper

"Almost always. Only in exceptional circumstances would I write a story on a paper I hadn't seen – for instance if the paper wasn't available, there was a detailed press release from a reliable source and a story had to be written in 30 minutes to meet a deadline I would reluctantly go without the paper. But I'd always want to speak to the author. It's vital.

"How much of it I read depends on how well it's written, the subject and how easy for a non-specialist to understand. In practice I'm unlikely to get much from reading an entire paper on an extremely technical [subject such as] cosmology or cell biology because the rest of it probably won't make much sense. I'll probably look at the abstract and conclusions. In those cases, interviews with the author and press releases are needed to fill in the gaps.

"But on public health studies, for instance, I'd expect to read the whole thing … Should have added that you need papers to check stats and risk ratios in press releases. Often they don't highlight the real story. Sometimes they get it wrong.

"Often if you can't get hold of the author of a paper on deadline, then the paper is the only way you'll get a quote. It's a question of crossing your fingers and hoping that they've written something clear and sensible.

"I've written far more stories where I've just seen the paper and not talked to the author than the other way round. It's about time."

Ex-science specialist on a national newspaper

"Often … it depends on circumstances (how close to deadline, how many words, if I had interviewed the scientists, how easy to get the paper etc.)

"Yes, particularly for major papers, when you need to get a comment (most rival scientists will not comment without seeing the original paper), find angles, work out who did what, check method, find animals used, find ideas for graphics/images etc. I would read the lot if a major paper but often made do with abstract, intro and conclusion."

Fergus Walsh - health correspondent, BBC news

"Always. The journal paper is unadulterated by the spin of any press release. I speed-read the paper and then focus on the key elements – sometimes that means reading sections again and again. Some papers are so technical and complex that they defy reading and you must rely on independent experts to talk you through it.

"Look at the Crick and Watson DNA paper or Doll on smoking – how brief, how succinct. If only authors now could write less and say more."

Nic Fleming – ex-science correspondent at the Telegraph. Now freelance

"I always try to read the paper when possible and usually read at least part of it. But if I have to summarise multiple papers in a small number of words for which I'm being paid not very much, I might not have time. In certain circumstances I might have to rely on a press release. I'm not a hobby journalist. I have a mortgage to pay and a child to feed, so editors and readers get the level of quality they pay for."

Specialist reporter on a mid-market tabloid

"I would say I almost always get hold of the original paper. The exceptions would be the odd occasion when I'm really pushed for time and the press release can be trusted.

"In most cases, the press release does not cover all the points I need to have clear, I'm not only questioned by the news editor for a broad brush outline but a sub for nitpicking detail (bless them).

"I read all of the paper most of the time. I'm a very fast reader. You never know when you're going to get extra info as background, clarification, context, confounding factors, statistical anomalies, references that are useful.

"I don't understand why original papers are not always attached to press releases (it can take up valuable time calling it in), I assume for reasons of computer space, when it's a near essential for a journalist's peace of mind."

Lewis Smith – ex-science specialist, Times. Now freelance.

"Nearly always. There are few occasions when I don't try to get the paper to read through. They are generally when the demands of time favour churnalism over journalism.

"The alternatives are usually to rely on press releases or even other press reports. Both have the potential of being skewed by self-interest. They can also include misinterpretations and misunderstandings.

"I like to make my own assessment of what the scientists are saying, and I'll often spot a nuance that has been missed or ignored in a press release. There are often elements that I will make more of than press releases do, which allows me to write a more individual report.

"Importantly, when asking scientists questions about their research it helps to have read their journal reports. Not only do I think that they appreciate it, but it makes for better directed questions.

"There are also occasions when I'll get a paper that no one else has written about – in the media or in press releases. On those occasions they are a crucial source of information.

"I'll read as much as I can understand in the time available. This means the abstract, introduction, conclusion and discussion sections will be read pretty thoroughly. I'll often skim through the methods and results because they generally don't contain the material I will quote or use as a basis for follow-up questions, but there are plenty of times when I read them in more detail."

Clive Cookson – science editor, Financial Times

"I think it is good journalistic practice always to read the original paper, though very occasionally there may not be time. The reason is that secondary reports of the study, such as in a press release, often miss out key features or interesting details. If I want to differentiate my story from dozens of others based on the same paper, I need to look for things that others might not have picked up."

John Von Radowitz, science correspondent Press Association

"Mostly. I always try to. Sometimes it's not possible due to time constraints. If a press release reveals glaring 'holes' that cannot be filled without reference to the paper, and I can't get hold of someone to speak to, I don't do the story.

"Press releases are not always right; they sometimes get basic facts wrong. Even when cleared by the scientist leading the research, they're not immune to hyping and spin. They often leave out facts that are important and provide balance.

"If I have time I'll always read the whole paper although some of it might be scanned quickly. Otherwise I'll focus on the summary at the beginning and 'discussion' section at the end if there is one. The more difficult a paper is, the more it has to be read."

Richard Black – environment correspondent, BBC news

"Virtually always. The only exception would be when pressed for time on a non-controversial topic. Most of the time I try to speak with the scientist as well.

"I usually read all of it, though sometimes the methods can be skim-read. It is vital to do so because the paper should give an accurate description of what was done, and why, and the actual conclusions reached. Press releases have a different job – to attract the interest of the press.

"There are journalists who proudly assert they never read peer-reviewed papers – and boy does it show. Time pressure is increasing all the time but in my view this is one thing we have to prioritise and not stop doing."

Broadsheet specialist correspondent

"Mostly. To understand the results of the study. Usually I only look at the intro and conclusion and graphs.

[If you don't read the original paper most or all of the time why not?] "Because I cannot understand the writing. It is often calculations etc. that are completely beyond my training. It's not about time constraints as I would need a PhD in statistics not an extra 20 minutes.

"OK, I don't really like reading science journals. To me it feels like quite lazy journalism waiting for a journal to drop and then re-writing it. I just find it more satisfying and interesting to talk to the scientist – if you can, surely that is the best way? Also, the scientist may have more to say when communicating with ordinary folk rather than other academics.

"It's nice to go through a paper to get an idea of the original study but frankly I always need help from the scientist to undertand it anyway. These papers are beyond doctorates! In all sorts of subjects! Even with training it would be difficult to comprehend them all. I think press officers should be ready to help you to speak to the scientist and explain the science.

"The journal paper is the last piece of the jigsaw, that you read afterwards when you have been give the tools to understand it properly. Then you can communicate it properly. If the audience want to read a journal they can, but they don't. They want to read a newspaper report that explains it clearly and in context."

Tom Feilden – science correspondent, Today Programme, BBC

"If I said 'always' that would be a fib, but it's still more than 'mostly'. I go to the paper to satisfy myself that the claims in the press release, or from the author/scientist who's tipped me off to the publication, are accurate and justified.

"I do it because I'm wary of taking a press release at face value. Although most do reflect the contents of the paper there's an understandable temptation to overemphasise the significance of the findings and I need to know if that's going on.

"To be honest I only rarely read a paper from beginning to end. I'll skim it, cherry-picking facts and figures and to get a sense of the important points. I'm much more interested in reflecting what the author intended rather than the press office.

"Because it's broadcasting we're much more dependent on getting an interview with the author, so some of the pitfalls are avoided. And while an outlandish scoop might tick a lot of journalistic boxes, I have to work this beat next week and if I come off looking stupid that doesn't do anything for my long-term prospects.

"Time constraints are important and so is easy access to a paper. If I can't get hold of the paper or the author in advance the most likely outcome is that we simply won't do the story."

Broadsheet specialist correspondent

"If it's a page lead, I'll normally try to get hold of it. If it's a summary I normally won't have time – spending anything more than an hour on those would mean I would have no time at all for proper journalism elsewhere. But, generally, summary length pieces are about clever chimps or intelligent dolphins or other animal magic stories. They generally don't gain a lot from fully reading the paper …

"Whether it is important depends on several factors. How detailed is the press release? Does it sound like it's hyping? How many words am I writing? How important or complicated is the story? If it's a story about a life-saving cancer drug then you need sample size, study group, and caveats/p values. If it's about the discovery of a new galaxy, or whatever, you really don't (although i often will). Then I would argue journalistic due diligence would be to try to chat to the scientists involved.

"I would normally read abstract and discussion, and skim the rest. If it's about quantum mechanics, there's really not much point in me reviewing the calculations …

"Ideally, we'd read all papers and phone the scientists. But, sometimes, it's 6pm and you have an hour to turn around 600 words. Then, choices become rather limited."

Specialist journalist on a mid-market tabloid

"Always read all of it. Do not trust press releases. Look specifically at the key findings, any hypotheses put forward in discussion and the methodology, especially sample size. Often press release has missed the best line.

"Amazed at how often we have to ask press officers for the paper – would say at least 70% of the time. They should send it automatically with press release.

"Sometimes tricky to get hold of scientific papers when don't have appropriate Athens password etc. and have to wait for press officer in America to wake up and send it. Would be great if they were much more easily accessible."

Lawrence McGinty – science and medical editor, ITV News

"I always try to read the original paper – and succeed about 75% of the time. For several reasons:

1. To check the press release is not full of flam (very rare)

2. To make sure the press release has not misled me by omitting some detail of the research, or omitting an important piece of context (much more common)

3. To check financial interest of authors

4. To make sure the authors' conclusions are broadly in line with the story I'm being sold (commonly they're not)."Of course, it depends who sent me the press release. Some are much more reliable than others and so if i'm pushed for time I tend not to read original papers from trusted sources."

Specialist reporter

"Virtually always, unless it's really not available – not online and the researcher is in Australia or something. We buy them online if PRs don't provide them, and have had rows about this with pharmaceutical companies who sometimes try not to give them out.

"There has been the occasional time that I've suddenly been asked to write something at 7pm, or do a late-night follow-up [on a story] from another newspaper that I haven't [covered], but would tell the newsdesk if I thought the source was unreliable.

"I think it's always worth looking at what the scientists have actually published and their data and methods, and they give you an idea of the previous literature on the subject.

"Also some press releases are full and interesting with lots of explanatory quotes from the scientist, but many are brief, and sometimes they don't highlight something from the paper which may be more interesting.

"I'll usually get through the whole thing, but the amount of time spent doing this depends on the day and how many other stories are on … it would be great if they were routinely attached to the emailed press release by university and journal press offices rather than request-only, if they are based somewhere with a huge time difference/we need it out of office hours."

Broadsheet specialist correspondent

"Always read the paper – but not always every bit of it, especially if it's a really long one or the technicalities aren't that relevant.

"Definitely read summary, intro, conclusion, but sometimes not a lot of the in-between – it depends on the paper, eg. for some the methodology will be not very important but for others the methodology will be the main point, etc.

"It is important to have a look at the original paper because you could be missing something otherwise.

"A lot depends on the journal where the paper appears – some are excellent at providing really good summaries of papers and then reading the paper itself is just about checking your understanding is the same, checking nothing is missing, checking for other interesting points, etc. But some are not and can even be misleading. And some make it easier to get hold of the authors than others.

"The ideal situation when it's a really big paper is when they do a press conference on it, either by teleconference or at the SMC [Science Media Centre], because then you get an in-depth reading of the paper and a chance to iron out all the questions etc."

Richard Gray – science correspondent, Sunday Telegraph

"Always. Generally I will read the abstract, introduction, and discussion first to get an overview of the research. I then read the results and methods in some detail to understand what the researchers have done to carry out the work. I usually follow this up with a discussion with the researchers themselves.

"I have had some bad experiences by relying on the information contained within press releases in the past. I will now always check the information in them against what is in a journal article. Often, I find there are better lines hidden inside the journal papers themselves.

"Due to the nature of working on a Sunday paper, I tend to hunt out stories directly from journal papers rather than getting press releases, so I have a tendency to read the original paper anyway.

"I tend to see press releases as a starting point, rather like a tip-off, for a story. I find the idea of churning out stories straight from press releases rather dangerous. It seems to be a source of some rather troubling errors. Even facts, figures and quotes in press releases should be double-checked in my opinion.

"A year or so ago I was sent a press release from a US University via EurekAlert that quoted a researcher from Brazil adding his backing to some research on the impact of climate change on forests. It turned out that the Brazilian researcher had not been contacted by the press office of the university, nor had he been asked if he could be quoted. He had sent some comments to the author of the paper in a private email which were then taken out of context and quoted in the press release without his permission. Understandably he was furious.

"Sadly the nice folks at EurekAlert didn't seem to bothered about this, but still get themselves worked up into a frenzy about embargo breaks on the basis that 'it might introduce inaccuracies'.

"Another recent example that fell into my inbox came from a non-science press release about an art installation/PR stunt in Trafalgar Square of a fake sun that was 30,000 times bigger than a football – clearly a ridiculous claim (this would give a circumference of more than 12 miles by my back-of-an-envelope calculations). Rather sadly this appeared in many of the national papers (including the Telegraph) unchecked.

"Of course, I cannot claim to not make errors myself and reading a paper can make a piece of research all the more confusing due to the way some things are phrased in the scientific literature, but I think everyone should be in the habit of scrutinising scientific papers. And this does not just apply to journalists, but the general public as well."

Mark Henderson – former science editor, Times

"Always. With a couple of very rare exceptions – when I am writing something that will almost certainly make only a nib [news in brief], or when exceptionally busy and close to deadline. But these cases are very exceptional.

"Press releases can be misleading – they may be hyped, they may miss the real story, or they may simply contain insufficient detail. You have to check that the press release is an accurate reflection of the science.

"I read as much of it as I can. Sometimes technical language will be beyond me, in which case you have to ask yourself whether it's really worth writing up. Or whether it's worth the investment in time involved in getting someone to explain it to you.

"[When I wrote a story without reading the paper], it was usually because I knew the story was unlikely to make at length, so time was better invested elsewhere."

On Thursday, Alice Bell – who chaired the scientists/media discussion at the Royal Institution – will present her roundup of unanswered questions from the debate. For more discussion of these issues, come to the UK Conference of Science Journalists on 25 June at the Royal Society in London

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion