Chapter 4. An examination of three ritual healers:

The Basque salutariyua, the French marcou and the Italian maramao

© Roslyn M. Frank

�Table of Contents

The following four documents include three pre-publication versions of a series of monographs

published in the journal Insula: Quaderno di Cultura Sarda. The fourth article was published in

2015 in the proceedings of a conference on bear ceremonialism, Uomini e Orsi. The articles

represent chapters in what is an on-going investigation into a pre-Indo-European ethnocultural n

substrate of Europe, a substrate whose presence is clearly visible in the performance art

encountered in many regions of contemporary Europe. The page numbers for each article, as

they appear in this file, are listed below (highlighted in grey). However, the reader is encouraged

to read the chapters in sequence since the material presented in the first one comes into play in

the next one, serving as the basis for further explorations to the topic under discussion.

1. Chapter 1. Recovering European Ritual Bear Hunts: A Comparative Study of Basque and

Sardinian Ursine Carnival Performances. Insula-3: Quaderno di Cultura Sarda (June 2008)

pp. 41–97. Cagliari, Sardinia. http://www.sre.urv.es/irmu/alguer/. [pp. 1–60 ]

2. Chapter 2. Evidence in Favor of the Palaeolithic Continuity Refugium Theory (PCRT):

Hamalau and its linguistic and cultural relatives. Part 1. Insula 4: Quaderno di Cultura

Sarda (December 2008), pp. 61–131. Cagliari, Sardinia.

http://www.sre.urv.es/irmu/alguer/. [pp. 61– 98]

3. Chapter 3. Evidence in Favor of the Palaeolithic Continuity Refugium Theory (PCRT):

Hamalau and its linguistic and cultural relatives. Part 2. Insula-5: Quaderno di Cultura

Sarda (June 2009), pp. 89–133. Cagliari, Sardinia. http://www.sre.urv.es/irmu/alguer/.

[pp. 99– 150]

4. Chapter 4. Bear Ceremonialism in relation to three ritual healers: The Basque salutariyua,

the French marcou and the Italian maramao.” In Enrico Comba & Daniele Ormezzano

(Eds.) Uomini e Orsi: Morfologia del Selvaggio. Torino: Accedemia University Press, pp.

41-122. [pp. 151–214]

5. Chapter 5. Hunting the European Sky-Bears: Revisiting Candlemas-Bear Day and World

Renewal Ceremonies. (in prep.).

6. Chapter 6. The pre-Christian origins of Zwarte Piet (Black Peter) and his European

relatives. (in prep.).

� Chapter 1. Frank, Roslyn M. Recovering European Ritual Bear Hunts: A Comparative Study of Basque and

Sardinian Ursine Carnival Performances. Insula-3 (June 2008), pp. 41-97. Cagliari, Sardinia.

http://www.sre.urv.es/irmu/alguer/

Recovering European Ritual Bear Hunts: A Comparative Study of

Basque and Sardinian Ursine Carnival Performances

Roslyn M. Frank

University of Iowa

E-mail: roz-frank@uiowa.edu

Homepage: http://www.uiowa.edu/~spanport/personal/Frank/Frankframe.htm

Everybody says, “After you take a bear’s coat off, it looks just like a human”.

Maria Johns (cited Snyder, 1990: 164)

“Lehenagoko eüskaldünek gizona hartzetik jiten zela sinhesten zizien.” (“Basques used to

believe that humans descended from bears”)

Petiri Prébende (cited in Peillen, 1986: 173)1

[…] the word does not forget where it has been and can never wholly free itself from the

dominion of the contexts of which it has been part.

M. M. Bakhtin (1973: 167)

Introduction

My interest in the Mamutzones dates back to 2002 when I was contacted by Graziano Fois,

a researcher from Cagliari, Sardinia. Using the Internet, he discovered that I had done

considerable research on Basque folklore and culture and wanted to consult with me

concerning a theory he had developed concerning the origin of the name of the

Mamutzones. He had been investigating this Sardinian cultural phenomenon for some time

and was looking at the linguistic component of it. More specifically, he was attempting to

1

The quote is from an interview conducted in the fall of 1983 with one of the last Basque-speaking bear hunters

in the Pyrenees, Dominique Prébende, and his father Petiri. It was the latter who among other things said the

following: “Lehenagoko eüskaldünek gizona hartzetik jiten zela sinhesten zizien” [“In times past Basques

believed that humans descended from bears”] (Peillen, 1986: 173).

� 2

identify the etymology of the root mamu-. As he pointed out, written documentation on the

Mamutzones and s’Urtzu (the bear) will not take us further back than the 19th century

where they are first mentioned. However, there is abundant toponymic evidence for this

root across Sardinia, and especially in the central part of it, a zone considered to be

somewhat more conservative in terms of the retention of older cultural elements. Therefore,

while written documentation on this phenomenon has a relatively shallow time depth, the

toponymic evidence suggests a different picture: a far deeper time depth, although not one

that can be dated with any precision. Stated differently, one avenue that might provide

further insights into the origins of the Mamutzones and s’Urtzu would be to trace the

etymology of the root mamu-.

Fig. 1. A typical Mamuthone. Source: http://www.tropiland.it/sardegna/Mamuthones.jpg.

� 3

Fig. 2. S’Urtzu. Source: Fois (2002)

Graziano laid out his theory to me in a short essay called “Liason entre Basque et Sarde

pour un possible racine *mamu /*momu /*mumu” (Fois, 2002b). In it he compared a series

of terms in Basque and Sardu which appeared to be cognate with each other, that is, their

phonological shape and semantic meaning coincide closely. I found what he wrote quite

intriguing, although until I read his article I had heard nothing about the Sardinian

Mamutzones and their bear.

By the time that I read Graziano’s essay, in 2002, I had already been investigating

Basque traditional culture for more than a quarter of a century and was well aware of the

etymology of the term mamu in Basque and its connection to a remarkable bear-like figure.

In fact, the word mamu is only one of several phonological variants of the name of this

ursine creature in Basque, while the names for the Carnival characters who appear to be

structural equivalents of the Mamutzones (Mamuthones or Mamuttones) are referred to by

� 4

terms such Mamozaurre, Momotxorro, Mumuzarro, Moxaurre, etc., expressions which

show similar phonological alternation in the root of the words (Frank, 2005a).2

Fig. 3. Momotxorros of Alsasua, Nafarroa. Source: Tiberio (1993: 58). Photo by Luis Otermin.

I would also include the Basque Joaldunak or Zanpantzarrak in the same category as the

aforementioned ritual performers.3 The term joaldunak translates as ‘those who possess

bells’, while zanpantzarrak is sometimes rendered as the “St. Pantzars”, although that

etymology is somewhat questionable. The performers in question are from carnivals

2

The first presentation I gave concerning this topic was in Cagliari, in 2005, in collaboration with Graziano

Fois.

3

With the advent of electronic media and the easy accessibility to digital photography and video, web pages

have sprung up across Europe displaying local traditions and performance art, cultural artifacts that before

were relatively inaccessible to researchers, except to regional specialists. As a result, in recent years the

Basques, too, have paid more attention to what they see as the ritual counterparts of their own performers in

other parts of Europe, including the Mamutzones. On January, 24, 2008, the newsletter produced by

Dantzan.com, an organization composed of a large number of Basque dance groups, included a comparative

study entitled “Joaldunak, Zarramacoak, Botargak eta Mamuthones-ak”. It contains several striking video

clips of performances from four locations in the Iberian Peninsula as well as from Sardinia and Bulgaria. The

video clips not only afford the viewer an opportunity to see the performers in action, they also contain

valuable ethnographic data: http://www.dantzan.com/albisteak/joaldunak-eta-abar.

� 5

celebrated in the villages of Ituren and Zubieta in Nafarroa. The performers wear two large

sheep-bells on their backs.

Fig. 4. Joaldunak bells. Source: http://www.dantzan.com/albisteak/joaldunak-eta-abar.

I should clarify that there are slight differences between the costumes of the Joaldunak de

Zubieta and those of Ituren. The main difference is that the former do not wear the

sheepskin over their shirts to cover their upper body, while those from Ituren do. Also two

smaller bells without clappers are attached to the sheepskin costume of the performers from

Ituren. These smaller bells are fixed to the back of the performer, slightly above the two

large sheep bells.

� 6

Fig. 5. Joaldunak of Ituren, Nafarroa. Source: http://www.ituren.es/es/. Photo by Ernesto Lopez Espelta.

Although the bells are not clearly visible in some of the photographs (below), the noise

they make can easily be appreciated in the following video footage taken during the

Carnival of Ituren and recorded on February 24, 2008:

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x4hcqm_carnavalituren_parties as well as in the video

footage of the same festival found at http://www.dantzan.com/albisteak/joaldunak-eta-

abar. As is obvious, these public performances take place during the day-time hours, rather

than at night. Today none of the Joaldunak performers wear masks and therefore their

identity is easily recognized. This contrasts with practices from times past where they

would hide their identity behind a mask made of kind of black fabric and they often

changed the timber of their voices. That way their identity was further disguised. In fact,

previously, the performers did not remove their costumes, not even their bells, during the

entire festival period, eating and sleeping with them on.

When watching the footage, the characteristic jerky gait of the Joaldunak should be

noted. As the folklorist and ethnomusicologist Juan Antonio Urbeltz (1996) pointed out,

the performers place their feet on the ground in an odd, non-human way, that is, the way

they walk imitates the rocking gait of a bear, i.e., a bear that is walking upright. By

� 7

watching the videos available at http://www.dantzan.com/albisteak/joaldunak-eta-abar, the

odd gait of the Joaldunak can be compared to the stylized way of walking that characterizes

the Mamutzones and the Botargak from the small village of Almirete, some sixty

kilometers northeast of Madrid, Spain. In Almirete, they celebrate this festival on February

2nd, a date known across Europe both as Candlemas and as Bear Day.4

Fig. 6. One of the Joaldunak of Ituren. Source: Tiberio (1993: 38). Photo by Luis Otermin.

4

For a detailed analysis of ritual performances associated with Candlemas Bear Day, particularly performances

encountered in the Pyrenean region, e.g., Zuberoa, cf. Frank (2001).

� 8

Fig. 7. Joaldunak of Zubieta. Source: Tiberio (1993: 35). Photo by Luis Otermin.

Fig. 8. Procession of Joaldunak. Source: http://www.pnte.cfnavarra.es/kzeta/ituren_erreport.htm.

� 9

Fig. 9. Joaldunak in Ituren, Nafarroa. Source: http://www.ituren.es/es/. Photo by Ernesto Lopez Espelta.

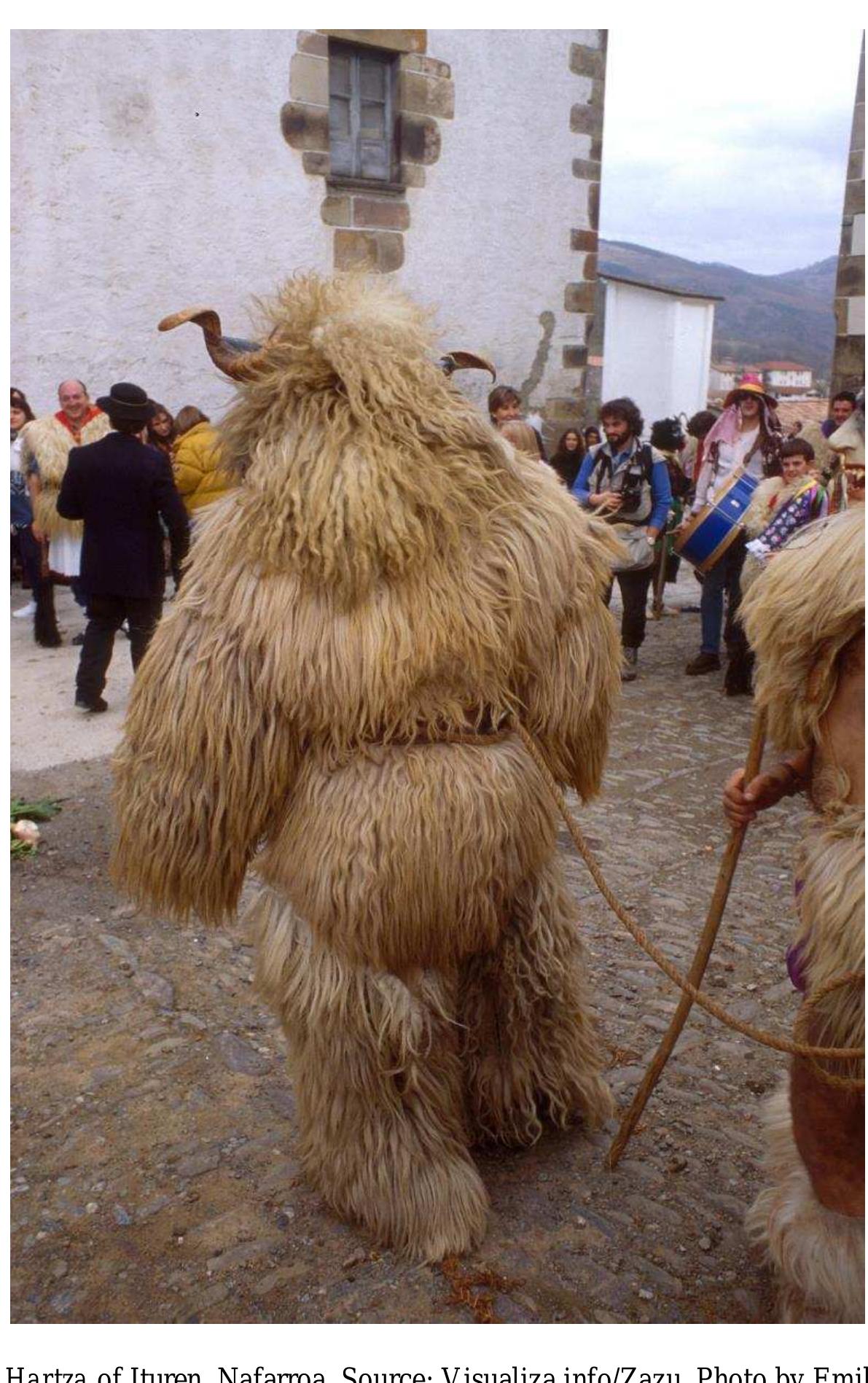

I would note that the Basque Bear or Hartza who is accompanied by these performers,

also has “horns”, as can be appreciated in the following photos from the festival in Ituren.

The costume is made out of sheepskin while the traditional headdress is constructed from

the head of a ram and has the horns exposed (Tiberio, 1993: 36).5

5

For more information on the Joaldunak, cf. http://basque.unr.edu/dance/pages/yoaldunak.htm.

� 10

Fig. 10. Hartza of Ituren, Nafarroa. Source: Visualiza.info/Zazu. Photo by Emilio Zazu.

� 11

Fig. 11. Hartza in Ituren, Nafarroa with its Keeper. Source:

http://www.pnte.cfnavarra.es/kzeta/ituren_erreport.htm.

Fig. 12. Hartza of Ituren, Nafarroa. Source: http://www.ituren.es/es/. Photo by Ernesto Lopez Espelta.

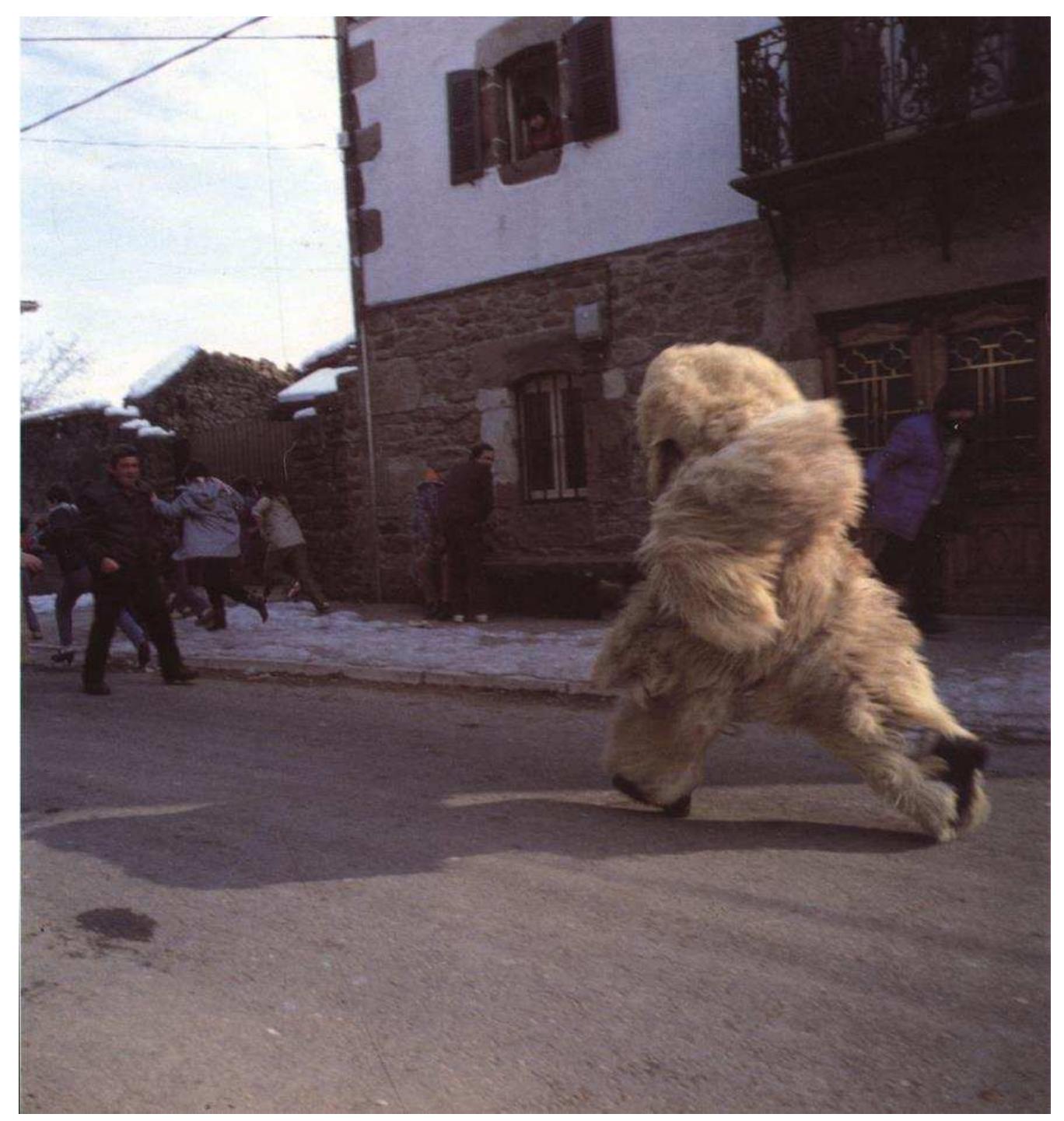

Today these actors regularly perform in public and in broad daylight. Divided into two

groups, they move along in single file, one after the other. They can also reverse direction,

an act initiated by the two lead dancers. This can be seen clearly in the videos listed above.

In other words, we are talking about a public performance constructed so that there are two

roles: the active role of the performers and a passive role of the other participants, namely,

the crowds of people who attend. On the other hand, even today the Hartza doesn’t respect

these conceptual boundaries, and constantly attacks the spectators, young and old alike.

� 12

Fig. 13. Hartza in Arizkun, Nafarroa, chasing bystanders. Source: Tiberio (1993: 71). Photo by Luis

Otermin.

Fig. 14. Another “horned” Hartza from Ituren with its Keeper. Source: Tiberio (1993: 14). Photo by Luis

Otermin.

� 13

In times past, however, the performances included what are called “good-luck visits”

(Frank, 2001, in press-a) where the actors in question, along with their bear, went about

paying visits often to quite isolated farmsteads where they would ask for contributions,

usually in the form of foodstuffs. Urbeltz describes the way that they would creep up on

their victims:

Para ello tapaban con yerba la boca del yoare [bell] al objeto de que no hiciera ruido. Caminando entre

los campos conseguían entrar en la casa a través de la cuadra; una vez en la cocina, con sigilo, quitaban

la yerba a los descomunales cencerros y comenzaban a caminar alrededor de la estancia con el

consiguiente espanto de niños y mayores. (In order to do this they stuffed the mouth of the yoare shut

with grass with the objective of keeping it from making noise. Walking through the fields they would

manage to enter the house through the stable [on the ground floor]; once inside the kitchen, with great

care, they would remove the grass plug from the huge sheep-bells and would begin walking about the

room which ended up scaring the children and adults). (Urbeltz, 1994: 230)

This description allows us to imagine times past when these masked performers marching

along single file, in the dark of night, accompanied by their Hartza, would have given a

very different impression than they do today, that is, as they slowly move along the public

roads and streets of Ituren and Zubieta, in broad daylight, and with their faces totally

uncovered.

In short, if we compare the performances from earlier times with those held today, we

can see that the division between spectators—the audience—and the actors was far less

rigid. Stated differently, the boundary between actor and spectator was totally dissolved

through the direct physical interaction between both groups. The frightening, indeed,

almost terrifying appearance of the intruders was emphasized by the strange black masks

they wore and the way that they disguised their voices—speaking in a whisper in some

locations, not speaking all or speaking in strange tongue that, supposedly, only they

understood (Hornilla, 1987: 24-27, 37-39). The intruders arrived at the farmstead, silently,

often in the dead of night, appearing before the householders without warning. Thus, the

sudden discovery of these wild, almost other-worldly creatures in their midst must have

terrified the householders to no end, at least initially, and, consequently, the intimidating

demeanor of the intruders must have left a deep and lasting impression on their hosts, that

is, on those living in the house, children and adults alike.

Another characteristic of these Basque belled-performers is the way that they emit a

rhythmic, low animal-like huffing sound, “huh, huh, huh, huh”, produced by inhaling and

exhaling rapidly, as they walk along. The sound itself is reminiscent of the characteristic

huffing sounds that bears make in the wild, when disturbed, nervous or otherwise distressed

(DeBruyn et al. 2004; Kilham, 2008). It is often understood to be a sign of aggression; that

the bear is about to launch an attack, whereas, in fact, it is associated primarily with what

� 14

is called a “bluff charge”, which is nevertheless extremely intimidating for any human,

even if the person recognizes that the bear’s action is intended more as a warning:

When a person gets too close to a mother with young cubs, the sow will usually display, letting the person

know her intent without having to attack. If the person disregards her signals, she may kick it up a notch

by cocking her ears, charging and vocalizing a face-to-face ‘huh, huh, huh, huh’. Often the sow will also

use a greatly modified false charge or swat to the ground in an attempt to persuade an intruder to back

away. These gestures constitute a motivational use of ritualistic displays. The intentional display is used

to convey a message or prevent an attack. Bears have great success in using these displays to intentionally

motivate people to drop food or knapsacks. […] The false charge is done in combination with other bluff

displays, like chomping, huffing and snorting. Depending upon the situation, this usually reflects the

bear's desire to delay or avoid direct confrontation. (Kilham, 2008)6

Should a bear decide to attack, it is silent, although such attacks against humans are rare.

While today very few spectators would be familiar enough with bear behavior to recognize

the significance of this ritual “huffing” of the performers of Ituren and Zubieta, in times

past when encounters with wild bears were much more frequent, the “huffing” sound would

have been especially meaningful and would have added another indication of the ursine

nature of the masked performers.

Linguistic evidence for the Bear Ancestor: Hamalau

In Euskal Herria (Basque Country) there is another aspect of the Hartza bear character that

needs to be addressed, namely, the fact that this creature forms an integral part of a complex

cosmogony of significant antiquity, one that holds that humans descended from bears, in

short an ursine story of origins that places bears at the center of the creation process. As

will be demonstrated in this study, in the case of Euskal Herria, the socio-cultural

embedding of this creature is so extensive that it affords us a mechanism for understanding

or at least for exploring the potential meaning of the performances in which this character

plays a major role. In addition, when examined with care the socio-cultural situatedness of

the Basque data opens up avenues for re-evaluating the meaning of the Mamutzones and

s’Urtzu, their performances as well as the semantic content of other Sardinian linguistic

artifacts sharing the same or a similar root, e.g., momotti.

6

Cf. also Kilman & Gray (2002).

� 15

Fig. 15. Mamuthones during the Feast of St. Anthony Abbot (January 17). Source:

http://imagocaralis.altervista.org/index.php?mod=04_Soci/Fabrizio/Mamoiada&inscomm=1.

Although this topic will be treated in considerable depth in the course of this study, at

the point I would mention that in Basque there is strange bear-like being who goes by the

name of Hamalau “Fourteen”, a compound composed of hama(r) ‘ten’ and lau ‘four’. As

will be explained shortly, Hamalau plays a central role in Basque traditional belief and

performance art (Perurena, 1993: 265-280). For example, variants of this term are

commonly used to refer to a frightening creature that parents call upon when their children

misbehave, i.e., the counterpart of the “babau” or “spauracchio” in Italian. The dialectal

variants of the word hamalau include mamalo, mamarrao, mamarro, mamarrua, marrau

and mamu, among others (Azkue, 1969; Michelena, 1987-). All of these variants show

“nasal spread”, that is, the word ends up having two /m/ sounds.

In order to understand what has taken place with the phonological shape of the

expression hamalau, we need to keep in mind that in many Basque dialects the letter /h/ is

silent. Therefore, in these dialects hamalau would have been pronounced as amalau (as it

is today in Batua, the Basque unified written standard). This means that because of the

phenomenon of nasal spread, the word ended up with two /m/ sounds, the /m/ which starts

the second syllable spread to the beginning of the word: amalau > mamalau. Also, I would

remind the reader that since Basque has no gender, a variant form such as mamalo should

not be interpreted through the grammatical lens of a speaker of a Romance language. In

� 16

other words, while the -o ending on these variants might appear (to a Romance speaker) to

be indicative of masculine gender, in Basque this is certainly not the case.

Then I would mention that in the case of the variant mamarrao, another common

phonological change has taken place: the replacement of one liquid, i.e., /l/, with another,

namely, with a trilled /r/, so that the last syllable /lau/ is pronounced as /rrao/. Finally, the

variant marrau demonstrates further phonological erosion, i.e., the loss of the second

syllable /ma/: mamarrao > ma(ma)rrao > marrao >marrau. In the instance of mamu,

additional phonological loss can be detected: (h)amalau >mamalau > mamarrao >

mam(arr)au > mamu.7 All of these linguistic processes will be treated in more depth in the

subsequent chapters of this study and compared to the Sardinian examples.

In the case of Sardinia, in addition to the Mamutzones and a variety of toponyms having

similar roots, there are numerous other words that are of interest. These have essentially

the same meanings but slightly different phonological representations. Here I refer to the

fact that the stem of the word varies in its phonological shape, demonstrating roots in

mamu-, momo-, momma- and marra-. In the case of the root form mamu-, there are

mamuntomo: “spauracchio”; mamuntone: “fantoccio”; mamuttinu: “strepito”; mamuttone:

“spauracchio, spaventapasseri”; mamuttones: “maschere carnevalesche con campanacci”;

mamutzone: “spauracchio” as well as mamus “esseri fantastici che abitanoi nelle caverne”.

In the instance of the variant of momo- we find: momotti: “babau, spauracchio”; mommai:

“befana”; mommoi: “babau, befana, fantasma, licantropo, orco, pidocchio, spauracchio,

spettro”; momotti: “babau, spauracchio”; marragotti: “befana, biliorsa, bilioso, fantasma,

mangiabambini, mannaro, orco, ragno, spauracchio, spettro”(Fois, 2002b; Rubattu, 2006).8

7

In Basque, some of the phonological variants associated with the semantic field of hamalau also refer to small

beings, tiny magical semi-human creatures, often helpful to humans but of a rather indefinite shape; they also

appear incarnate in the form of insects, as if the former as well as the latter were viewed as capable of shape-

shifting, undergoing metamorphosis, taking on a disguise, e.g., as a larva might be understood to shape-shift

when it becomes a chrysalis and then turns into a butterfly. For example, mamutu carries meanings related

to “putting on a masque” or otherwise “disguising oneself”; to “becoming enchanted, astonished, astounded”

or “put under a spell”; more literally it means “to become a mamu” while the verb mamortu, from the root

mamor-, means both “to become enchanted” and “to form oneself into a chrysalis” or “to become an insect”

(Michelena, 1987-, XII, 56-59). Hence, in the same word field, we find two types of magical creatures. On

the one hand there are the large, strange beings that are sometimes invoked by adults to frighten children and

get them to behave, and, on the other hand, another set of creatures, much smaller, usually helpful although

at times mischievous. The latter are said to wear a red tunic or pointed hat and otherwise dress in black.

Anyone familiar with the qualities of elves, pixies, fairies, brownies, and leprechauns which abound in Celtic

folklore would see a resemblance. As mentioned, they also sometimes take on the shape of insects. They go

by the name of mamures or mamarros in some Spanish-speaking zones; in contrast their Catalan counterparts,

are called maneirós and appear as black beetles (cf. Jose Miguel Barandiaran, 1994: 79; Gómez-Legos, 1999;

Guiral, Espinosa, & Sempere, 1991). As Fois (2002) has observed, these semantic extensions are reminiscent

of certain terms in Sardu, a topic that will be taken up in the next chapter of this investigation.

8

The English counterparts of these terms are as follows: from the root mamu-, mamuntomo: “scarecrow”;

mamuntone: “puppet”; mamuttinu: “racket, clamour, noise”; mamuttone: “scarecrow”; mamuttones: “masked

� 17

Also, I would mention that the names used for the Basque ritual counterparts of the

Mamutzones reveal similar phonological correspondences. Thus, in the case of the Basque

and Sardinian materials, we have two types of data that can be compared. One type consists

of the linguistic artifacts themselves, that is, lexical material found in each language, while

the other type of data is embodied socio-culturally in traditional belief and performance

art, again as manifested in Euskal Herria and Sardinia, respectively. The former data set is

linked to the latter in the sense that the meanings of linguistic artifacts are “cultural

conceptualizations”, socio-culturally situated and shared by a community of speakers. Thus

the cultural conceptualizations should be understood to be “distributed” not only across the

community of speakers at any given moment in time, but also across time and space, in the

sense that they pass from one generation to the next. In other words, the aforementioned

lexemes and their connotations provide us a means of reconstructing the ways in which

they were used by speakers in times past as well as their prior cultural embodiment in social

practices.

Given that we are talking about linguistic artifacts, beliefs and performance art that have

been transmitted orally, they have not been subjected to rigorous documentation or

interpretation until quite recently. In short, the traces they have left in the written record

are scant. Therefore, a different approach must be employed in order to develop a

methodology that does not rely solely on written texts, but is capable, nonetheless, of

reconstructing and interpreting the cognitive and material artifacts under analysis. In short,

we are dealing with cultural conceptualizations that need an interpretative framework. So

the first step is to see whether the comparative approach, originally proposed by Graziano

Fois, can provide us with new insights into the Sardinian materials (Fois, 2002a, 2002b,

[2002]). Naturally, at this stage in the research, our conclusions should be understood as

tentative.

With respect to the question of methodology, in the case of etymological reconstructions

which deal with cultural conceptualizations and that are in turn socio-culturally entrenched,

we are faced with the task of tracing the evolutionary path taken by these artifacts over

time, but without the aid of written sources. Stated differently, if examined with care

linguistic artifacts can reveal the imprints of the collective thought processes of a given

speech community, thought processes that shape and eventually give rise to the meanings

associated with the linguistic artifacts at any given point in time. In other words, since

performers wearing bells; masks”; mamutzone: “scarecrow”; mamutzones “masked performers wearing

bells” as well as mamus “fantastic beings who inhabit caverns”; from the variants momo- and mammo-,

momotti: “hag, witch, scarecrow”; mommai: “hag, witch”; mommoi: “bogey man, hag, witch, phantom,

spectre, were-wolf, ogre, louse, scarecrow”; momotti: “bogey-man, scarecrow”; and from marra-,

marragotti: “hag, witch, imaginary beast, phantom, baby-eater, were-wolf, ogre, spider, scarecrow, spectre”.

� 18

language itself is a distributed form of cultural storage, every time a word is used it is used

in a specific context, and often in relation to a particular type of event. This way the original

meaning(s) associated with the word can be reinforced, or changed ever so slightly.

Over time, a word can acquire new meanings, nuances that were not there in the

beginning, while retaining its older meanings. Hence, by examining the semantic record it

is sometimes possible to reconstruct these prior thought processes and the socio-cultural

embedding of the linguistic artifact. When the linguistic artifact also has a performance

component, e.g., when it is also the name of a class of ritual performers, the performers

and their actions become a kind of material anchor for the artifact: the meaning of the

artifact is off-loaded so to speak onto the performer, his costume and actions. Thus, the

meaning of the linguistic artifact can be transmitted across time by means of these ritual

performances.

In the same fashion, past technologies and even belief systems can leave their mark in

the linguistic record, i.e., in the form of linguistic artifacts. For instance, today many people

still use the word “icebox” to refer to a “refrigerator”, a clear reference to an earlier stage

in which food was kept inside a “box” that contained large blocks of “ice”. Even though

the referent of the term “icebox” is no longer literally an “ice-box”, i.e., a box for ice, the

word has survived, attached to an analogically and functionally similar object. And because

it has survived, even if we have never actually seen the prototype of an “icebox”, we can

imagine what it must have been like because of the information provided to us by the word

itself.

In a similar manner, once the etymology of the dialectal variants of the word hamalau

is identified, i.e., mamalo, mamarrao, mamarro, mamarrua, marrau and mamu, among

others (Azkue, 1969; Michelena, 1987-), we are better able to explore the meanings

associated with the term hamalau (Perurena, 1993: 265-280), the socio-culturally

embedded significance of the bear-like character called Hamalau and the performance art

that is associated with him. In other words, the socio-cultural situatedness of the terms,

including the variants of the terms and the way their meanings have been off-loaded,

provides us a means of reconstituting the earlier meanings and socio-cultural significance

of the expressions. Furthermore, if we find correspondences between the Basque terms and

those found in Sardu, this comparative data will add another dimension to the discovery

process and another source of information for interpreting the word field in a more

comprehensive fashion.

At this juncture the following comments by Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza (1984: 139)

are relevant: “Confidence in [evolutionary] reconstructions is built by the development of

multiple lines of evidence that generate independent support for a particular interpretation.

� 19

Ultimately, it is the growth of new evidence in individual fields and the creation of

expectations for findings in other fields that generate a dense network for evaluating a

reconstructive hypothesis.” Therefore, before entering into a detailed discussion of the

linguistic artifacts themselves, the first step is to outline the various lines of evidence that

will be brought to bear on the problem, particularly those that will be treated in this chapter

of the study.

The Bear Ancestor: Hamalau

When I first decided to do fieldwork in Euskal Herria it was evident to me that I would

need to learn Euskara (Basque). Soon after I had gained enough proficiency in the language

to carry on a basic conversation, a strange thing began to happen to me. People would take

me aside and tell me the following in a low voice, as if they were sharing a very important

yet almost secretive piece of knowledge: “We Basques used to believe we descended from

bears.” The first time someone told me this, I had no idea what I should say in response. I

found the statement totally amazing. Yet over and over again the same thing happened to

me. People, who didn’t know each other, who had no contact with each other, ended up

telling me the same thing.

Finally, I came to the conclusion that I had come across a key piece of data. I just didn’t

know what to make of it. Subsequently, I tried to find references to this Basque belief in

bear ancestors. But all my attempts were futile. There was nothing in the literature; nothing

written down anywhere. The belief seemed to have survived only orally, though oral

transmission, passing from one generation to the next, without any outsider ever noticing

it and writing it down. Later I would discover that the ursine genealogy was connected to

a rich legacy of belief and cultural conceptualizations.

It would not be until the late 1980s that I would come across a book with a concrete

reference to this belief. In fact, the first written documentation of what my informants had

been telling me was published in 1986, in a brief article by the French-Basque ethnographer

Txomin Peillen (1986), entitled “Le culte de l'ours chez les anciens basques”. In it he

reports on an interview he conducted in Zuberoa (Soule) with one of the last Basque-

speaking bear hunters in the Pyrenees, Dominique Prébende, who was 48 years old at the

time. Dominique’s 83 year old father, Petiri Prébende, was also present. Peillen begins by

explaining the circumstances of the interview:

Au cours d'une enquête sur la chasse traditionnelle, il y a deux ans, nous décidâmes d'interroger un des

derniers chasseurs ayant participé à des battues d'ours brun des Pyrénées à Sainte-Engrâce, dans le Pays

de Soule [Zuberoa] en Pays Basque. (Two years ago, while carrying out a survey of traditional hunting

practices, we decided to interview one of the last hunters who had taken part in the brown bear hunts of the

� 20

Pyrenees at Sainte-Engrâce [Santa Garazi], in the province of Soule [Zuberoa] in Euskal Herria [Basque

Country].) (Peillen, 1986: 171)9

Fig. 16. The seven provinces of Euskal Herria, the historical Basque Country, span France (light yellow)

and Spain (rest of the map) Names in this map are in Basque. Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basque_Country_(historical_territory).

He then records the following comments of Dominique:

Dominique Prébende nous déclara que son groupe de chasse, avait pratiqué fréquemment la battue à

l'ours; il ne put ou ne voulut pas nous dire combien d'animaux furent ainsi abattus. Il protesta qu'il n'en

avait pas tués personnellement, tout en ajoutant qu'il craignait moins l'ours que le sanglier. Poussé à

s'expliquer sur cette chasse, il nous déclara que tuer l'ours porte-malheur "ür gaixtoa ekharten dizü" et

que l'homme qui le fait ne donne rien de bon "eztizü deuse hunik emaiten", dit cet homme de 48 ans.

(Dominique Prébende told us that his group of hunters had frequently taken part in bear hunts; he couldn’t

or didn’t want to tell us how many animals [bears] were killed this way. He objected that he had never

personally killed any, quickly adding that he feared a bear less than a wild boar. Pressed to explain more,

the 48 year-old man confided in us, declaring that to kill a bear brought bad luck "ür gaixtoa ekharten

dizü" [lit. “it brings you bad luck”] and that the man who did would receive nothing good from it

"eztizü deuse hunik emaiten" [lit., “it doesn’t give you anything good at all”].) (Peillen, 1986: 171)

9

The term battue is used generically to refer to hunting, but it also refers to a particular hunting practice, e.g.,

for wild boar, which involves a group of hunters moving silently through the woods, often separated into two

lines, moving along in single file. And then suddenly one group would begin to make all sorts of racket to

flush out the game, driving it in the opposite direction, toward the other row of hunters. In times past, this

was done using various kinds of noisemakers including bells (Caro Baroja, 1973: 192-197).

� 21

Peillen speaks of a special prayer that was recited by the hunters to protect themselves

from the dangerous influence of bears:

Toutefois il semble que les anciens savaient se protéger du maléfice précédent. Notre père […] nous

racontait que les chasseurs d'autrefois disaient une prière avant de se rendre à la Chasse à l'Ours.

Dominique Prébende, également, le vit faire à des hommes aujourd'hui décédés, et nous avons peu

d'espoir de recueillir cette prière ‘Hartz otoitzia’ [The Bear prayer]. (However, it appears that the old

hunters [hunters from before] used to know how to protect themselves from this curse. Our father […]

told us that in times past hunters would say a prayer before setting off on a Bear Hunt. Similarly,

Dominique Prébende witnessed men, now deceased, perform this supplication, though we have little hope

of recovering the prayer today, i.e., the ‘Hartz otoitzia’ [The Bear Prayer]). (Peillen, 1986: 171)

While killing a bear, or admitting that one had killed a bear, brought bad luck, the

bear’s paw was highly esteemed for it was said to bring good luck. 10 Indeed, it acted to

protect the person from the “evil eye” and other illnesses: Speaking of this practice of

preserving the bear’s paws, Peillen adds this comment:

Cette coutume de les garder est commune aux chasseurs d'ours sibériens et amérindiens, pour qui la patte

est un porte-bonheur; de même manière inexplicite elle est gardée par les chasseurs basques. Ce rôle

de la "patte à griffes" dans la magie basque s'observait au début du siècle, lorsque pour préserver les

enfants du mauvais œil on suspendait à leurs cous des pattes de blaireaux. (The costume of preserving

them [bear paws] is common to Siberian and Native American bear hunters, for whom the paw is a

good-luck amulet; in the same inexplicit manner, it is preserved by Basque hunters. The role of

“paws with claws” in Basque magic was observed at the beginning of the century [20th century], a

time when protecting young children from the evil eye, involved hanging badger paws around their

necks.) (Peillen, 1986: 172)

With respect to the prophylactic qualities attributed to badger paws, I would note that

the etymology of the various terms used today in Basque for the badger goes back to

hartz “bear”. The terms are nothing more than phonologically reduced or otherwise

altered forms of (h)artz-ko, the diminutive form of (h)artz ‘bear’. Pronounced as

(h)arzko, the compound term refers to a ‘small bear, little bear’. Given the

characteristics of badgers, their fearlessness and willingness to defend their turf at any

cost, this lexical choice would seem to be taxonomically appropriate. For example,

Llande (1926: 94) gives the following variants for Zuberoa (Soule) and Lapurdi

(Labourd) and Nafarroa Beherea (Basse-Navarre): arsko(S, N), azku (S), azkuñ (S),

hazkon (N), azkonarro (L) and azkoin (L, N) (cf. also Frank, in prep.-a). Azkue (1969,

I: 84) lists the Zuberoan word for “badger” as hartzku, which translates transparently

as “little bear”.11

10

For a discussion of the widespread nature of this custom, cf. Mathieu (1984).

11

The protective powers of the “little bear” (badger) are discussed by Barandiaran: “En Ataun (Guipuzcoa),

había costumbre de colocar pieles de tejón sobre los cuellos de los bueyes, que uncidos al yugo iban a ser

expuestos al público, como al conducir el carro de boda y en otras ocasiones semejantes, pues existía la

creencia de que así quedaban a cubierto de toda mala influencia de los aojadores” (“In Ataun (Gipuzcoa)

there was the custom of placing badger furs over the neck of oxen that were yoked to be exhibited in public,

for example, to the wedding cart or in other similar occasions, since there existed the belief that in this way

� 22

Later on in the interview, another aspect of the belief system comes into view: the

human-like appearance and behavior of bears.

Dominique Prébende nous déclara qu'il ne put manger de l'ours, qu'il y goûta et vomit au souvenir de

l'animal qu'il avait dépouillé et qui lui semblait avoir une étrange morphologie humanoïde. Il nous apporta

la patte qui se trouvait dans sa chambre, pour confirmer ses dires en ajoutant "dena jentia düzü", c'est

tout à fait un être humain, et le père qui se trouvait assis à proximité commenta avec humour "latzxago",

un peu plus rugueux. (Dominique Prébende told us that he couldn’t eat bear meat, that when he tastes

it, he vomits at the thought [memory] of the animal that he had skinned and that it seemed to him to

have a strange human-like shape. He brought us the paw that was kept in his room, in order to confirm

what he had said, adding that "dena jentia düzü", it’s just like a human being, and his father who was

seated nearby, commented with humor, “latzxago”, [but] a little more rough.) (Peillen, 1986: 171)

I would add in passing that in Basque the expression latzxago is the comparative form of

the adjectival root latz. The meaning of this word is not limited simply to “rugueux” or

“rough”, but rather describes something that is “terrible, frightful, fear-inspiring” as well as

“powerful” and “extraordinary”. Hence, Dominque’s father is correcting his son, adding that

the bear is not simply “like a human”, but rather more terrible, powerful and extraordinary

than human beings.

At this juncture, Peillen reveals the key factor that was motivating his informants to

speak as they had about the bear, insinuating that it had human-like characteristics. And

again, as we will see, the informant is reluctant to speak in public about this particular

belief. In fact, it is only after the tape-recorder is turned off that he confides in his visitors,

assuming that this way the secret knowledge he is going to share would be kept safe from

the prying ears of outsiders. We need to remember that Petiri was speaking in Basque to

other native speakers of Basque. Hence, it would seem that he waited to tell them the most

important part until he felt confident that the knowledge would not be disseminated

indiscriminately among those who were not Euskaldunak (Basque-speakers), i.e., he

waited until they turned their tape-recorder off. Referring the belief in a bear ancestor,

Peillen states:

Cette croyance décrite pour les Amérindiens et les Sibériens, n'est pas décrite pour l'Europe à notre

connaissance, bien que tous les éléments précédents la fasse pressentir. C'est ainsi qu'alors que nous

avions éteint le magnétophone, terminé notre enquête, Petiri Prébende nous déclara tout de go:

“Lehenagoko eüskaldünek gizona hartzetik jiten zela sinhesten zizien” (les anciens basques croyaient que

l'homme descendait de l'ours). Prié de répéter ses propos il ajouta que l'homme est fabriqué à partir de

l'ours. Il nous donnait la clef des croyances précédentes. (To our knowledge, this belief described for

Native American and Siberian peoples hasn’t been described for Europe, even though all the preceding

elements make one suspect its presence. There is also the fact that when we had shut off the tape-recorder,

ending our interview, Petiri Prébende suddenly told us: “Lehenagoko eüskaldünek gizona hartzetik jiten

zela sinhesten zizien” (“Basques used to believe that humans descended from bears”). When we asked

they would be protected from all bad influences of those who might cast the ‘evil eye’” (José Miguel

Barandiaran, 1973, V: 292). For additional information on this and related topics involving the prophylactic

properties of the “little bear” (badger), cf. Frank (in prep.-a).

� 23

him to repeat his remark, he added that humans were created by the bear. He had given us the key to the

previous set of beliefs.) (Peillen, 1986: 173)12

The last statement by Petiri concerning the fact that humankind “est fabriqué à partir de

l'ours” is probably a literal French translation of the Basque sentence “Gizona hartzak egina

da”.13 The expression could also be rendered as: “The bear created humankind”. Or,

expressed more somewhat more elaborately, “Our human origins go back to the bear who

created us.” When examined more closely, this cosmogenic belief in bear ancestors

resonates strongly with a hunter-gatherer mentality, that is, with what would be a

Mesolithic mindset, and not with the agricultural world view characteristic of Neolithic

pastoralists and farmers. Moreover, we see that the persistence of this ursine cosmology is

found not only in the folk memory of Basque speakers who are no longer emotionally

committed to the tenets of the belief system, but also in the minds of individuals like Petiri

and his son Dominique whose comments suggest that at least a residual true belief in the

Bear Ancestors still survived up to the end of the 20th century. In the sections that follow

we shall discuss other evidence—other types of cultural survivals—relating directly or

indirectly to this ursine cosmology.

A Central Component of the Cosmology: Bear Ancestors and the Celestial Bear

At first glance a cosmology that holds that humans descend from bears strikes one as odd,

especially to those of us accustomed to having anthropomorphic high gods, i.e., to

scenarios in which the divine being or beings are portrayed in human form. Nonetheless,

rather than being particularly unusual, it is a common genealogy for belief in a bear

ancestor has informed the symbolic order of hunter-gatherer peoples across the globe

wherever ursine populations have been present.14 In Europe, where primates were absent,

humans shared their habitat areas with bears and apparently saw themselves reflected in

this intelligent creature, whose skinned carcass, i.e., divested of its fur coat, the bear’s body

is remarkably similar to that of the body of a human being (Shepard, 1995; Shepard &

Sanders, 1992). In fact, Finno-Ugrians affirm that, once its fur coat is removed, a female

bear has the breasts, hips, legs and feet of a young woman (Praneuf, 1989: 9), while in

12

The phrase l'homme est fabriqué à partir de l'ours offers challenges to any translator since a completely

literal translation of it is rather difficult. It might be glossed into English in a number of ways: “man was

formed/shaped from/by bears; “from the bear came mankind; “the bear created/forged humankind” or more

loosely “humans descend from bears” or even “the lineage of humans sprang from the bear”.

13

Obviously, Petiri uses the term gizona which literally means ‘the man’, but in this context it means “humans”

or “humankind”.

14

Among human populations who shared habitat areas not with bears, rather with primates, the latter were

often seen as their ancestors (Mathieu, 1984; Shepard & Sanders, 1992).

� 24

some locations elaborate ritual ceremonies accompanied the act of “undressing” the bear,

most particularly the “unbuttoning” of its coat (Krejnovitch, 1971: 65).15

In addition, the animal’s incredible memory of landscape and keen sense of smell and

hearing gave it a distinct advantage over humans when it set out to hunt the same animals

and plant foods as its human descendents. Indeed the bear's hearing is so acute that at 300

meters it can detect human conversation, and it responds to the click of a camera shutter or

a gun being cocked at 50 meters. Also, we must remember that humans and bears are

foragers, omnivorous creatures who have been stuck in the same ecological niche for

hundreds of thousands of years, competing for the same food sources, salmon runs, berry

patches and honey trees (Shepard & Sanders, 1992).

Undoubtedly humans were impressed not only by the bear's uncanny ability to overhear

human conversations, but also by its small, almost human-like ears, facial expressiveness,

ability to walk upright on the soles of his feet, as humans do, as a well as by the animal’s

great manual dexterity.16 Also, in contrast to other temperate mammals, the female nurses

her young holding them to her breasts, which are located on her chest rather than her

stomach, just as a human mother does.

In short, bears and native peoples lived together on the continent of Europe for

thousands of years. Both walked the same trails, fished the same salmon streams, dug roots

from the same fields, and year after year, harvested the same berries, seeds, and nuts. The

natives came face to face with bears when both coveted the same berry patch, for instance,

or when a hunter, bringing help to pack home an elk he had killed, discovered that a bear

had buried the carcass and was lying on the mound. Sometimes the hunter fled, sometimes

the bear. The relationship was one of mutual respect (Rockwell, 1991: 1-2).

However, among the indigenous peoples of Europe there is evidence that the

relationship was far more complex. Bears were often central to the most basic rites of these

groups: the initiation of youths into adulthood, the sacred practice of shamanism, the

healing of the sick and injured, and the rites surrounding the hunt (Praneuf, 1989;

Rockwell, 1991; Shepard & Sanders, 1992; Sokolova, 2000; Vukanovitch, 1959). The

striking parallels that traditional peoples have identified between humans and bears,

traditions and practices found in many geographical regions of the world, have been studied

at length, particularly by those who are concerned with the belief systems of hunter-

gatherer societies. (Praneuf, 1989; Rockwell, 1991; Shepard & Sanders, 1992). Yet little

15

Krejnovitch's meticulous fieldwork which he carried out in 1926, 1927, 1928, and 1931, shows the

advantages that accrue when linguistic materials are utilized as tools of interpretative analysis.

16

Because of his mode of walking, the bear's footprints are remarkably similar to those left by human beings.

For this reason, in the Pyrenees, the bear is often referred to as pedescaous (pieds nus), i.e., “he who walks

barefoot” (Calés, 1990: 7; Dendaletche, 1982: 92-93).

� 25

serious attention has been paid to the possibility that in Europe there are still survivals of

this ursine genealogy, survivals that that might well date back to an earlier hunter-gatherer

symbolic and cultural order; survivals that today take the form of traditions, oral tales and

ritualized performance art. In the case of Western Europe some of the most profoundly

ingrained spiritual traditions and folkloric survivals of this ursine belief system have been

identified among the Basques as well as in the Pyrenean-Cantabrian zone where ritualized

bear hunts are still celebrated today.

Indeed, as we have seen, Petiri Prébonde’s words reiterate what must have been a wide-

spread belief in the not too distant past—at least among rural Basque-speakers:

“Lehenagoko eüskaldünek gizona hartzetik jiten zela sinhesten zizien” (“The Basques used

to believe that humans descended from bears”). Moreover, other evidence suggests that

this highly entrenched belief system might have been widespread in other parts of Europe,

for example, in Sardinia. Given that, until quite recently, this traditional lore has been

transmitted from generation to generation almost exclusively through oral practices and

performance art, Basque culture provides us with a remarkable window onto what appears

to be a much older and more complex European symbolic order that was grounded in this

ursine genealogy.

In this respect, we need to recall that the significance of the elderly Basque man's

comments about humans descending from bears is reinforced by those of his son who stated

that, although a seasoned bear hunter, he had never been able to eat bear flesh. The mere

smell of it made him want to vomit because “dena jentia düzü” (“it’s just like a human

being”). Cognitive parallels from North American Indians provide further insight into these

statements. In the Yukon, the Tlingit said: “Grizzlies are half human.” The Ojibwa often

referred to bears as anijinabe, their word for Indians. Likewise, the Yavapai of Arizona

said, “Bears are like people except that they can’t make fire”. Many plains and

southwestern tribes, including the Yavapai, would not eat bear meat because they believed

it was like eating a person's relative (Rockwell, 1991: 3-4). We find a similar sentiment

expressed by the Native American story-teller Maria Johns who is cited in Snyder (1990:

164): “Everybody says, ‘After you take a bear’s coat off, it looks just like a human.’” Bears

were humans, but they wore heavy fur coats.

In fact, outside Europe we also find that many hunting tribes thought of bears as the

shamans of the animal world and believed the animals’ hairy skin, paws and long claws

possessed therapeutic virtues. According to Yavapai myth, at the dawn of time the first

great shaman was Bear. Coexisting with these mythic narratives was a universal belief

among northern hunters that bears possessed powers analogous to those possessed by

shamans. Many said that bears changed their form to become humans, other animals, or

� 26

even inanimate objects. And in turn, those shaman healers who had the bear as a spirit

helper wrapped themselves in the skins of bears, wore necklaces of bear claws, painted

bear signs on their faces and bodies, and smoked pipes carved in the shapes of bears. In

their medicine bundles they kept bear claws and teeth and other parts of the animal. They

used bear claws and gall and bear grease in their healing ceremonies. They ate the plants

bears ate and used them as their medicines. They danced as they thought bears danced and

they sang power songs to the animal (Rockwell, 1991: 63-64).

At the beginning of the 20th century, as we have noted, in the Basque region of the

Pyrenees, bear paws were still highly esteemed as well as badger paws and claws, the latter

animals being classified taxonomically in the Basque language as a “little bears”. Perhaps

because of the difficulties imposed by the bear paw's large size and weight, in order to

protect children from the “evil eye”, the small paws of badgers, remarkably similar in shape

to bear paws, were hung from children’s necks as amulets (Peillen, 1986: 171-172).

Moreover, since contact with the bear itself was especially effective in terms of obtaining

the benefits of its curative powers, until about fifty years ago, in the Pyrenees it was still

common for the bear and his trainer to make annual visits to the villages where they were

warmly welcomed. Parents brought their children so that they could be placed on the back

of the bear who, under the care of the bear trainer, would take exactly nine steps. In this

manner parents were able to protect their children from physical illnesses and, in addition,

insure that they would be well behaved (Dendaletche, 1982: 91).

The belief that attributed similar curative powers to the bear also guaranteed the positive

reception of bear trainers all across the Balkans (Vukanovitch, 1959). In fact, there is

evidence that these bear doctors even made regular house calls to cure the sick and protect

the households from harm. In this sense, the visitation brought good luck to the household.

However, there is reason to believe that similar rituals were performed—with real bears—

across much of Europe and indeed there is documentary evidence that, earlier, even

monasteries were directly involved in training young bears who would go about with their

trainers to conduct these healing ceremonies. In short, these activities formed part of what

are called “good-luck visits”.

The possible diffusion of these healing practices across Europe can be judged, at least

to some extent, by the fact that schools were set up to train young bears to carry out their

duties. For instance, in Ustou and Ercé in Ariège (Midi-Pyrenées) we discover two of the

most well known of those institutions of higher learning where little bears were sent to be

educated and trained, often at public expense. The schools continued to function into the

20th century, more concretely up until World War I. Indeed, earlier the teachers and future

bear trainers constituted a highly structured fraternity based in the Pyrenean zone of Ariège,

� 27

while their pupils ended up performing throughout Europe (Bégouën, 1966: 138-139;

Praneuf, 1989: 67). Upon graduation the ursine pupils were brought to the town square for

a remarkable public ceremony (Praneuf, 1989: 68-69).

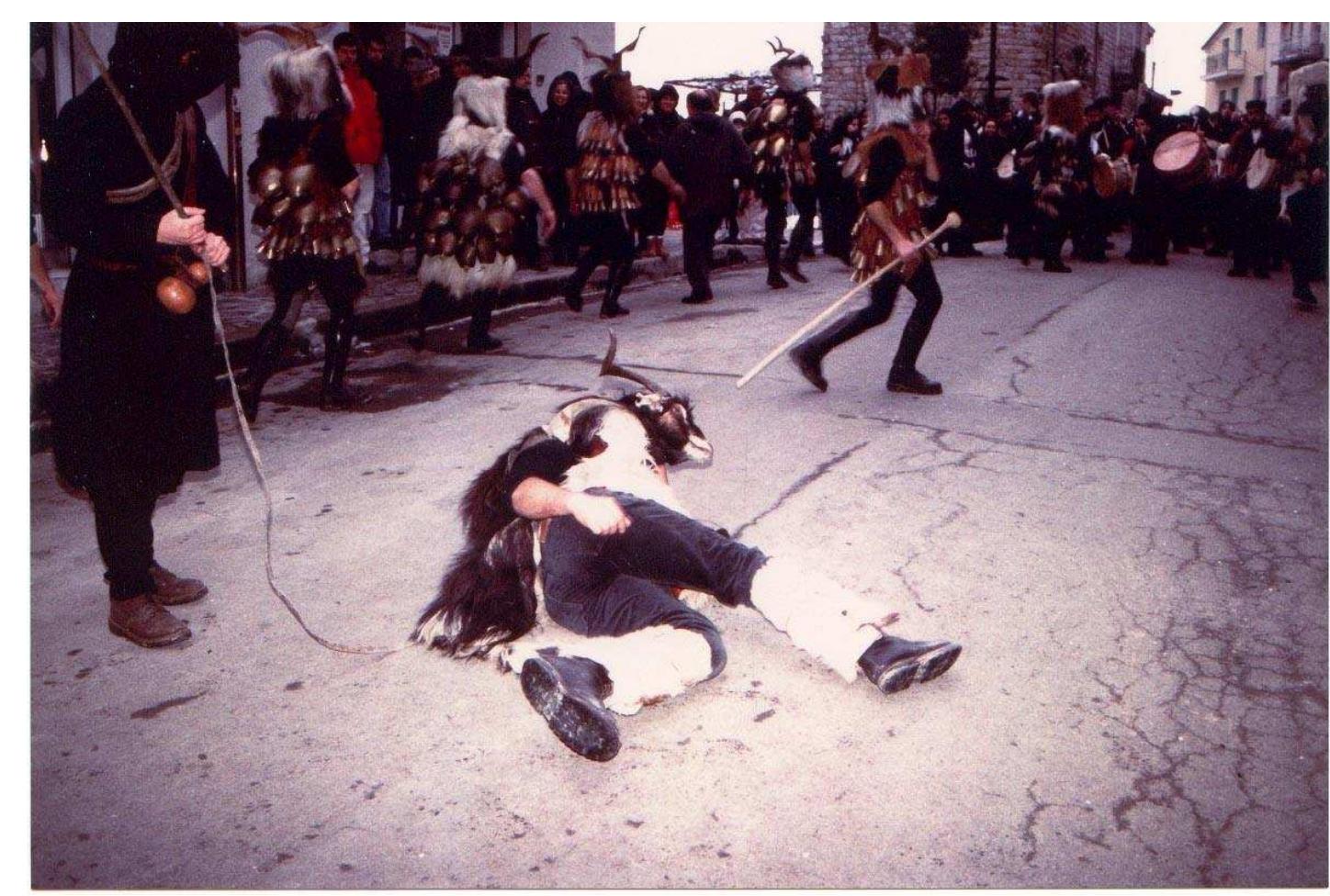

From the descriptions of the feats that the young bears had to learn in order to graduate

from these bear academies, we can see that the pupils were taught specific tricks, among

them that of falling down dead on command and then jumping up once more, again on

command. This feigning of death and subsequent resurrection of the bear was an essential

component of the “good-luck visits”(Praneuf, 1989: 69), a topic we will take up shortly.

While the aforementioned examples of bear academies are based on data drawn from

the Pyrenean region, in the northeast of France, in the Bas-Rhine at Andlau, there is

documentation concerning training bears at a Christian site that was inaugurated in the

ninth century, the Abbey of Andlau. Although nominally Christian, the legends connected

to the location strongly suggest a deeply rooted belief in the sacredness of bears. The site

in question is linked to a miracle about a bear. Supposedly, as a result of the miraculous

event, those inhabiting the abbey began to house bears inside their quarters. The villagers

of the area brought a loaf of bread each week to offset the costs of feeding the ursine

lodgers. Up until the French Revolution, bear-trainers from this zone of Alsace also had

the privilege of free lodging and a stipend of three florins and a loaf of bread.

Even today, next to the crypt of the tomb of the officially recognized saint of the

Abbey, Saint Odile, one can see the figure of a bear, carved in stone, resting on one of the

pillars (Clébert, 1968: 325-328). Yet one suspects that in earlier times the Christian

saint’s silent companion may have played a more active role in the rites celebrated at that

sacred site. In fact, one suspects that the location in question may have served as a

breeding ground for tame bears and bear trainers, as a place were the members of the

guild met and exchanged information (Gastau, 1987). Perhaps further research would

reveal the existence of other religious sites, inhabited by bears and their keepers,

scattered across Europe (such as the sanctuary of St. Remedio in northern Italy). It should

be remembered that in Medieval Europe the bear-keepers often performed in the

company of a troupe of masked actors, musicians and jesters, going from village to

village to conduct their “good-luck visits”.

� 28

Fig. 17. Bear leader and musicians. Source: engraving from Olaüs Magnus, Historia de gentibus

septentrialibus. Rome 1555. Reproduced in Michel and Clébert (1968: 329)

Another interview: Evidence for a belief in the celestial bear

In the case of Europe, because of its physical appearance and great intelligence, the bear

was, in fact, the animal that most closely replicated a human being. However, in contrast

to its human relatives, the bear seemed to be capable of dying and being resurrected from

a death-like sleep in the spring of each year. Evidence from many native peoples

demonstrates that this ability has been perceived by humans as one of supernatural, even

mystic, proportions.

Among the Basques, belief in the sacredness of the bears as well as their role as

ancestors of humans persisted into the latter part of the 20th century, as we have seen in

the case of the 1983 interview with Dominique and Petiri Prébende. Similar

documentation, perhaps of an even more remarkable nature, is encountered in another

unusual interview conducted slightly over a hundred years earlier, in 1891. This time the

informants are not Basque bear-hunters but rather two Basque bear-trainers. In the

interview the informants speak of the special powers of bears and the sacred relationship

holding between their ward, an earthly bear, and a Celestial Bear who is conceptualized as

a sort of ursine divinity. This remarkable document consists of a brief report by an English

folklorist by the name of Thomas Hollingsworth who was vacationing in the French Basque

region. There in the town of Biarritz he happened to run into two bear-trainers, a man and

his wife, accompanied by their bear. His published report documents the interview that he

conducted with them (Hollingsworth, 1891).17

17

I am greatly indebted to Evan Hadingham for bringing this interview to my attention over twenty years ago.

� 29

The text sheds additional light on the conceptual schema underlying the belief in an

ursine genealogy found among Basque people as well as on certain celestial aspects of the

belief system itself. The informants were Navarrese Basques whose first language was

Euskara (Basque). The Englishman communicated with the pair in Spanish since they knew

no French. That the first language of the two informants was Esukera is a conclusion easily

drawn from the introductory remarks of Hollingsworth who begins by addressing the

readers of the English journal Folk-Lore:

Can any reader of Folk-Lore throw any light on a superstition prevalent apparently among the Basques

of Navarre and the Aragonese of the Pyrenees, to the effect that the bear acts as a sort of watch-dog to St.

Peter at the gate of Heaven. My informants are two Navarese [sic] Basques, a man and woman whom I

saw exhibiting a bear in Biarritz. I have no doubt that, if I could have spoken Basque, I could have

extracted much more information than I did, but it was difficult for them to speak Spanish, the only

language except their own with which they were at all acquainted.18 (Hollingsworth, 1891: 132)

Hollingsworth states that initially the couple was shy and reticent and that it required a

good deal of persuasion on his part to win their confidence even in the slightest degree.

The interview, as reported by Hollingsworth, provides information concerning the role of

the Celestial Bear as the guardian of the Gate of Heaven. Through the comments of the two

Basque informants, we see that bears were viewed as extraordinarily intelligent animals,

so intelligent in fact that they once ruled the earth. Also, according to the two bear keepers,

bears are capable of understanding human speech, even Euskara.

In the interview Christianized celestial lore, mixed with elements from deeper strata of

the conceptual schema relating to the veneration of a Celestial Bear, can be detected. The

couple utilizes what Lienhard (1991) has defined as hybrid discourse where two different

cultural codes or schema are manipulated simultaneously. One element drawn from the

earlier schema is the emphasis placed by the bear trainers on the presence of wolves in

Hell. In fact, wolves are portrayed as adversaries of bears in the folk belief of the Iberian

Peninsula (Díaz, 1994).19

In Hollingsworth’s report the two bear guardians demonstrate profound respect for their

ward, although they never overtly mention any belief on their part in a bear ancestor. Given

the significance of Hollingsworth’s text, I shall cite the entire section in which he talks

about the interview:

18

The fact that the two had no knowledge of French suggests that they lived not on the French side of the

border, but rather on the Spanish side or at least that at some time in the past they had had more contact with

Spanish speakers. Otherwise, if they had resided on the French side of the border, it is more likely that they

would have known some French and probably no Spanish. Another inference that might be drawn from the

linguistic skills of the two Basque speakers is that they exhibited their bear primarily in locations where

Basque was the language spoken, and consequently would have had little need for using either Spanish or

French in their daily communication.

19

I am greatly indebted to Joaquín Díaz, Director of the Ethnographic Museum “Joaquín Díaz” of Urueña,

Valladolid, Spain, for this insight.

� 30

They told me that their bear, when they were not travelling about, lived with them in their hut in the

mountains, and that they were always careful to treat him kindly and feed him well. For example, if they

had not enough of fish (which they looked upon as a luxury) for themselves and the bear, the latter must

be fed and satisfied first. They declared that the animal understands all that is said about him, and observes

and comprehends any household work, trade or occupation which may be going on; “and that is the reason

that a bear who has lived with men should never be allowed to return to the forest and mountains, for he

will tell the other bears of what he has seen and learnt, and they, being very cunning, will come down

into the valleys, and by means of their great strength, added to the knowledge they have thus gained, will

be able to rule men as they did before!” (Hollingsworth, 1891: 132-133) [emphasis in original]

Hollingsworth was unfamiliar with the meaning of the reference to this earlier time

when bears supposedly ruled the earth. The reference to such a past epoch could refer to

the mindset that humans must have had long before the invention of firearms, at a point in

time when humans were far out-numbered by bears, yet shared mountain trails and salmon

streams with them. Far from feeling superior to these furry and very intelligent creatures,

humans must have been keenly aware of the possibility of an unexpected encounter and

therefore probably paid close attention to the habits, territorial ranges and feeding patterns

of their ursine cohorts. Moreover, according to field work conducted by Dendaletche

(1982: 95), in the Pyrenean region of Barèges, popular belief holds that formerly the

country was governed by five bears, each of which was in charge of a different district of

the zone. Humans and other creatures were obliged to render homage to their ursine rulers,

their ancestral kin. Undoubtedly the Basque bear-trainers' remarks, cited by Hollingsworth,

hearken back to a similar preterit cognitive framework.

Consequently, the reverent attitude of these two bear keepers underlines the fact that the

bear was deeply respected among the Basques. He was treated with similar reverence

across both America and Eurasia in times past, as is evidenced in the case of rites for the

dead bear celebrated until recently in Lapland, Alaska, British Columbia and Quebec. “All

across North America, Indians have honored bears. When northern hunting tribes killed

one, they spoke to its spirit, asking for its forgiveness. They treated the carcass reverently;

among these tribes the ritual for a slain bear was more elaborate than that for any other

food animal” (Rockwell, 1991: 2). As Shepard has observed, there is evidence of a wide

and ancient distribution of bear ritual. It is present in virtually every country of Western

and Eastern Europe, in Asia south to Iran, and among many of the Indian nations of the

United States, even into Central and South America (Shepard & Sanders, 1992: 80).

With regard to the animal’s uncanny abilities, the Asiatic Eskimos, for example, held

that during the festival of the slain bear, the bear’s shadow-soul could hear and understand

the speech of humans and men, no matter where they were (Shepard & Sanders, 1992: 86),

while the Tlingit said, “People must always speak carefully of bear people since bears [no

matter how far away] have the power to hear human speech. Even though a person murmurs

� 31

a few careless words, the bear will take revenge” (Rockwell, 1991: 64). Analogous beliefs

are found among the Ket (Yenesei Ostyaks), an Ugric-speaking people of Siberia, with a

rich tradition of bear worship, who believe that the bear is chief among animals, that

beneath its skin is a being in human shape, divine in wisdom. For them the bear was

invested

with the capability of understanding the speech of all beasts as well as of man. Besides, they fancied that

though the bear in summer was dull of hearing because of the rustling of leaves, in autumn or winter,

however, it was a very dangerous to speak ill of the bear or to boast of successful bear hunting. ‘Should

you speak badly of him one day or the other, and go hunting and find a good place, a bear will rise from

behind a tree suddenly and grab you with his paw.’ (Alekseenko, 1968: 177)

Thus, the Basque bear keepers' words echo a similar belief in the bear's ability to

understand human speech. And, far from describing him as a cuddly pet, the Basques'

comments, represent the bear as a familiar yet awesome being, in a fashion comparable to

that of northern peoples for whom he is “un animal intelligent, habile, humain, familier et

redouté” (Mathieu, 1984: 12).

Among Finno-Ugric peoples and Native American groups, the bear is viewed as

omnipotent and omnipresent. He has the power to hear all that is said. For this reason

hunters would avoid mentioning the bear’s real name, choosing rather to address him with

euphemisms. That these might have been the qualities attributed to the European Celestial

Bear and his earthly representatives, appears to be demonstrated in social practice by the

semantic taboo existing among Slavic and Germanic peoples. This led them to avoid

mentioning the bear’s real name, an avoidance pattern which, in all likelihood, stemmed

from a profound adherence to the tenets of this animistic cosmology. The substitute term

utilized in Slavic languages was “honey-eater”, while Germanic tribes preferred to call him

the “brown one”, an expression that gave rise eventually to the English word “bear”, linked

etymologically to the words “brown” and “bruin” (Glosecki, 1988; Praneuf, 1989: 28-32;

Stitt, 1995).20

Hollingsworth concludes his report with these pertinent revelations:

I endeavored to learn when this sad state of affairs existed [when bears ruled humans], but could only

ascertain that it was antes—before, in other times. “El Orso,” [sic] said his keepers, “es el perro de Dios,

el perro de San Pedro [the bear is the dog of God, the dog of Saint Peter]; he is very wise and thoughtful;

he sits beside the blessed saint at the gate of Heaven, and if those who seek to enter have been cruel and

unkind to bears in this world, the saint will turn them away, and they will have to go and live in hell, with

the devils and the wolves.” “Que hay más por decir!” concluded the woman, “el orso es el perro de Dios

[the bear is the dog of God].” The bear's name was Belis. I spell it as it was pronounced. Throughout the

20

Specifically the PIE etymon is *bher-, “bright, brown”, gave rise to the Old English form bera, and

eventually to the Modern English word bear. The word “bruin” is a cognate of this group, often used in

English to refer not to the color “brown” but to bears themselves ([AHD], 1969: 1509).

� 32

conversation the peasants would constantly interrupt themselves to speak to the animal,21 assuring me

that he perfectly understood all that was said. (Hollingsworth, 1891: 133) [emphasis in original]22

These last remarks by the couple merit a closer analysis. As I have noted, we are dealing

with a hybrid discourse where the tenets of Bear Ceremonialism are interwoven with those

of Christianity. There is also a topological overlapping between the two systems: there is

spatial configuration with a higher, afterworld, situated above, where the soul of humans

goes and where the person’s actions here on Earth will be submitted to a final judgment,

before the soul is allowed to enter heaven. In this case, the blending of the two belief

systems ends up positioning the bear as “the dog of St. Peter” or as “the dog of God”, sitting

next to the Saint at the gate of heaven. In other words, the “bear” takes on the characteristics

of a “guardian”. However, when examined with more care, we see that the questions that

St. Peter addresses to the new arrival deal with the way the person has treated bears. Thus,

we might say that St. Peter is acting on behalf of the bear figure, sitting silently beside him,

“very wise and thoughtful”. Stated differently, St. Peter is in charge of interrogating the

new arrivals concerning whether they have treated earthly bears with proper respect. In this

way the soul’s entrance into to Heaven is conditioned by the way the person has interacted

with bears on Earth. Even though the bear is called “el perro de St. Pedro” or “el perro de

Dios”, expressions that give deference to St. Peter or God as if these Christian actors were

the superior figures, in reality, because of the way the scene is structured, ultimately, it is

the silent figure of the bear that ends up determining whether the soul will be admitted to

the Other World.

This type of hybrid discourse is a rather typical result of what happens when two belief

systems become fused; where the older system survives as a substrate element within the

new system. In these circumstances, it is not unusual for the older spiritual figure to survive,

but often only after being assigned a more peripheral role. The figure now shows up seated,

silently, beside the new spiritual authority, or otherwise demoted to a lower level of

importance, visible, nonetheless, to those who chose to reflect more upon the implications

of the co-location of the participating elements. This situation is an example of a

phenomenon called contested ritual agency.

21

Since the two Basques spoke Basque to their bear, at this juncture, what they were saying to the bear, that

is, what they were telling it in Basque, was more likely a translation or at least a summary their ongoing

conversation with Hollingworth. Or if we assume that they believed the bear was already following the

conversation in Spanish—that is, the conversation between them and Hollingworth—they might have been

directing additional comments to the bear, in Basque, and therefore including him in the conversation. From

the text itself, this point is somewhat unclear.

22

From Hollingsworth’s attempt at a phonetic spelling of the bear's name as Belis, it appears more likely that

the bear’s name was Beltz. To an English ear this might sound like belis, whereas in Euskara the word beltz

means “black” and is a common nick-name for black animals.

� 33

In recent years increased attention has been paid to this concept of contested ritual

agency, particularly in cultural studies where two belief systems have been in prolonged

contact with each other (Eade & Sallnow, 2000). More specifically, the term refers to

manner in which symbols of identity are often skillfully manipulated by a given cultural

group. It is commonly employed to refer to the manner in which two opposing groups of

ritual specialists interact, one group protecting the older belief system while the members

of another group act as proponents of the new system. Over time this confrontation sets up

a contest with respect to the manner in which meaning is assigned to the symbolic artifacts

in question. Thus, the interpretation of the symbolic artifacts—which is at the center of this

process of meaning-making—depends on the way that the different groups adjust to each

other over time. In some instances, the older interpretation of the artifacts is retained, albeit

in a modified form, although the old interpretation can also disappear from view entirely.