Editor's Note: This article was originally published on February 17, 2014.

Sept. 21, 2013, 11:28 p.m.

27 minutes after launch

It's a quiet night on Kwajalein Island. It's always quiet here. The atoll, which the military calls "Kwaj," lies in the deep Pacific, 2400 miles southwest of Honolulu. Only 1000 people live on the 6.6-square-mile island chain, and nearly all of them work at military installations. On the evening of September 21, most of those people are manning consoles and watching video screens, radar returns, or streams of telemetry data.

Between 1946 and 1958, the U.S. conducted 67 nuclear bombs tests on these islands. These days, Kwaj is owned by the Republic of the Marshall Islands under "free association" with the United States. That means Washington pays for social services and cleanup costs on the islands. In exchange, the Marshall Islands allows free use for military testing. That testing no longer involves the detonation of real bombs. Instead, this is the site of the United States' dress rehearsal for nuclear war.

Tonight, in the autumn of 2013, three dummy nuclear warheads are headed for Kwaj. They're hundreds of miles away but closing fast. Each of six-foot-long triangular wedges blazes a trail of glowing plasma formed by the air friction of hypersonic flight. Soon the warheads will splash down just off the coast of the atoll and complete this intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) test, which the Pentagon calls Glory Trip 209.

July 19, 2013

66 days to launch

During Frontier Days in Cheyenne, an annual celebration of the spirit of the West, Warren Air Force Base opens its chain-link gates and invites the public inside. That's why 1st Lt. Lucas Rider of the 90th Operations Support Squadron is spending his Saturday chatting with rodeo fans who came to gape at mockups of ICBMs.

The jovial airman—an Eagle Scout and former intern on 'Oprah's Search for the Next TV Star'—puts a friendly face on Warren's secretive military operation. But his upbeat personality betrays a deadly serious job: 24-year-old Rider is one of the airmen who awaits the order to launch a nuclear missile. Every 24 hours, a fresh two-man crew boards an elevator and lowers into a capsule, where the airmen monitor the health of nuclear missiles waiting in silos scattered across the landscape. The message they await is called an "emergency action message." It would mean that the pair insert keys and turn them to launch.

On this day, Rider is aboveground chatting up the locals when he spots the approach of his task force commander, Lt. Col. Erik Mulkey, who pulls Rider aside for a quiet conversation. "Are you ready to head to California for two months?" Mulkey asks. The young airman's response comes quickly: "I can be, Sir." Two weeks later, Rider is on a plane heading southwest.

Rider has been chosen for a Glory Trip.

Three times a year, the Air Force randomly selects a Minuteman III ICBM from the missile fields, removes the nuclear ordnance, trucks the missile to California, loads it with telemetry packages, and fires it at the Kwajalein atoll, 4700 miles away. Some airmen call these test flights the Super Bowl for ICBM crews.

The Glory Trips are designed to test the missiles, but have the added benefit of boosting the morale of the missile crews and maintainers who keep watch on America's nuclear arsenal. They could use a lift. An internal Air Force study by RAND Corp., obtained by the Associated Press, found that the men and women who man America's nuclear weapons suffer from "burnout." It's not hard to see why. These airmen live on remote airbases, endure Personnel Readiness Programs that scrutinize their personal lives, handle ceaseless drills and tests, and see any infraction—like leaving nuclear proof blast doors open inside a launch capsule—as if it was a national security crisis. And America's ICBM professionals had a particularly rough year in 2013. Missile wings generated headlines after they failed readiness reviews. The Pentagon relieved two senior leaders involved with ICBMs of duty for personal misconduct, including the major general in charge of all land-based nukes.

But Rider does not come off as demoralized. The young airmen hadn't even heard of ICBMs before joining the Air Force. Now he is one of the men with his hands on the switches of the most powerful weapons ever created. And two months from now, on Glory Trip 209, he'll shoot one halfway across the planet.

Aug. 23, 2013

31 days to launch

Rider leans against an aluminum railing at Launch Facility 10, eyes fixed on missile silo door. There is a rhythmic clinking of metal teeth catching on metal gears, the sound of the hydraulic winching system slowly opening the hatch. The 110-ton concrete-and-steel hatch covers an empty tube that's large enough to accommodate a 5.5-foot wide, 60-foot-tall ICBM. Rider has spent long hours studying missiles, but very little time in their presence. "Knowing that I'm going to key-turn on it in less than a month is indescribable," he says.

Rider is flanked by a handful of other young Air Force personnel, all watching the dark eye of the silo open, the beginning of the long process of loading the missile into its firing tube. Behind them is an idyllic California backdrop—scrub-covered hills, an occasional palm tree, and a stretch of beach white with foam from the Pacific surf. These sincere but amiable twenty-somethings are Air Force ICBM launch crews from Warren and Minot Air Force Bases. Here at Vandenberg Air Force Base, 71 miles north of Santa Barbara, they are called "key turners from up north," meaning they hail from one of the three missile fields in Montana and Wyoming where America keeps its 450 ICBMs.

America's only land-based ICBM is the venerable Minuteman III. These workhorses were to be replaced in 2020, but Congress and the Obama administration in 2007 decided to keep the weapons on alert until 2030, when these weapons will be 70 years old. The Pentagon has spent more than $7 billion on ICBM renovations since 2007, including new missile engines. Analysts from the Air Force and Department of Energy are particularly concerned about the three-axis gyros that orient the missile, which are called the pendulous integrating gyroscopic accelerometers (PIGA). They're costly to build, costly to repair, made of exotic materials and demand a skilled workforce to maintain them. No surprise, then, that the Air Force is paying so much attention to these during tests.

The Minuteman III to be fired in GT-209 travelled by truck from Wyoming to California, and today will be loaded into the tube. (The nosecone and its payload—nuclear or dummy warheads—always travel separately.) Missile handling teams (MHTs) load and secure the Minuteman III inside a white 69-ft tractor-trailer called a transporter-erector, which will back into place with the missile loaded tip-first into the trailer as it prepares to lower the 79,000-pound missile into the silo. It's like loading a the biggest bullet you've ever seen into the barrel of a single-shot pistol.

The trailer slowly tilts, lifting the missile upright. It's hard to watch this without thinking about Optimus Prime. Everything happens deliberately—the way things need to be done when your cargo is filled with enough solid propellant to blast a payload into space (or kill everyone in the silo if it were released at once). All the while the missile needs to be coddled. A scratch, dent, or nick on the surface would be photographed, monitored and observed to see if the skin was suffering a propagating crack. Every tool is clipped to a tether before it gets close to the silo's now-open maw. Anything that could compromise the structural integrity of the Minuteman III could be a showstopper for GT 209.

At the end of the half-hour process, the trailer stands at 90 degrees with its open rear door perched over the silo door. "At the wing, we don't usually get a chance to see a missile emplacement because we're in the capsule communicating back and forth with the maintenance teams," says GT 209 missileer Nathan Larson, of the 321st Missile Squadron at F.E. Warren. "It's a really cool experience."

It takes all day to load the silo with the three-stage rocket. The week after the task is completed, the missile handling teams will again "penetrate" the silo and outfit the Minuteman with its guidance and instrumentation ring—along with three dummy warheads called Joint Test Assemblies.

The GT-209 mission patch, which everyone wears on the left arm, is a grey isosceles triangle depicting a snarling, three-headed hound. The name under the animal reads "Cerberus." It's a not-so-subtle nod to the three dummy warheads, each representing a nuclear warhead capable of destroying a good-sized city.

Maj. Pat Baum, of the 576th Flight Test Squadron, notes that Cerberus is "the three-headed dog that guards the gates of hell." It's a nice touch.

Sept. 21, 2013, 1:00 a.m. PST

120 minutes to launch

ICBM test launches happen in the early hours of the morning, U.S. time, so they disrupt as few people's lives as possible. Airplane traffic has to be diverted on the West Coast and Hawaii. Boat traffic on the California coast shuts down. Even the local train line, built 60 years before Vandenberg Air Force Base was established, stops. It's like a large part of the world pauses for liftoff.

There are many eyes fixed on Vandenberg tonight. Scores of civilian test engineers will scrutinize the missile engine's stats and stresses. The Missile Defense Agency also monitors the warheads Members of an Air Force "reliability scoring panel" will use a slew of sensors to judge the accuracy of the warheads. The Department of Energy also monitors the test since it is tasked with verifying the effectiveness of reentry vehicles.

The eyes of other nations are on the launch as well; they like to know exactly when the U.S. is going to launch dummy nuclear warheads, and so staffers from the U.S. State Department's Nuclear Risk Reduction Centers notify counterparts around the world of the impending test. Even with proper warning, an ICBM launch can raise hackles. On September 3, 2013, operators of the Russian early-warning radar detected two "ballistic objects"—a missile body and the warhead that separated from it—following a trajectory toward the Eastern shore of the Mediterranean. The Russians thought it might be the start of combat operations against Syria. It turned out the launch was part of an announced Israeli missile defense test and the Russians were tracking a dummy target.

The world still takes notice when a ballistic rises from the ground. The end of the Cold War did not eliminate the threat of nuclear weapons—the threat has expanded to new nations wielding longer-ranged missiles. Those with nukes want better missiles to launch them, and many of those without them are at least considering creating them to grab the bargaining power in world politics that comes with being a nuclear nation. Russia still has 1800 nuclear weapons, and launch-tested four ICBMs in a single day—two on land and two from subs—in late October 2013. China's growing arsenal might include as many as 60 long-range missiles that can reach anywhere in the United States. That number does not include the Chinese submarine-launched ICBMs that some experts feel will be operational this year. North Korea has long-range missiles, and an underground detonation last February may be a sign that nation is developing a small nuke suited for a missile warhead.

The Pentagon maintains that the promise of nuclear counterattack is the only certain way of preventing their use against America and its allies. And so professionals in the ICBM world talk about deterrence a lot. Maj. General Michael Carey, then-Commander of the 20th Air Force, which controls all land-based nuclear missiles, summed up the institutional view when he visited the Popular Mechanics offices in July 2013. "We keep a lid on World War III," Carey said. "And for less than $5 billion a year. The U.S. Postal Service lost three times that in 2012 alone." (The Air Force relieved Carey of command for personal misconduct three months after the visit.)

Sept. 21, 2013, 1:30 a.m.

90 minutes to launch

A launch countdown is really just a series of smaller countdowns. Inside the ICBM Launch Support Center (ILSC) within Vandenberg's gates, uniformed members of the 576th Flight Test Squadron and civilian contractors are seated at their consoles, reading data flashing on the screens. The airmen wear green flight suits. The civilians are dressed casually, in jeans and slacks, but most wear ties. All are speaking jargon over headsets and going through the exhaustive checklists, checking battery voltages, pressure readouts, and telemetry feeds from another building on the base.

The ILSC fits about 15 people. Two large, black-and-white video screens dominate the front of the room. One shows the silo door at LF-10; the other alternately displays weather radar images and video feeds from Kwaj. In between the screens are digital clocks that display countdowns and a red-yellow-green bar of lights indicating the launch range status. Right now, the light is yellow, as it should be.

Reams of data unspool from a Microline 184 dot-matrix printer. Every so often, one of the civilians folds the paper and places it on an ever-growing pile. The out-of-date printer—like the Minuteman III and its launch infrastructure—was designed in the 1960s. If it works, don't replace it.

The Launch Director, Capt. Denise Michaels, is in the middle of this scrum of missileers. She's the authority in the room and the point of contact between ILSC and the ultimate head of the missile-shot: Col. Lance Kawane, commander of the 576th flight test squadron. He is standing vigil in another building, inside a large room called the Western Range Operations Control Center. The WROCC looks like launch control rooms at other spaceports—massive video screens and countdown clocks looming over dozens of people in front of consoles, with senior-level officials like Kawane in a separate room overlooking the operation.

The third leg of launch control is the crew in the capsule, a dozen miles from the base's buildings. There, 1st Lt. Rider and three other key turners from up north are pulling an alert, the oddest and (hopefully) most exciting work shift of their careers. For the past week, the launch crews have been entering the launch control centers as if the missiles were carrying live nukes.

The work stations at Vandenberg have been fully manned since 11 p.m. Potluck food stands in rows. Discussions of football fill the quiet times. Every minute closer to launch brings more systems checked, more radar brought online, more safety systems enabled—and more risk of pauses, called holds. The hope is that the planned 3 a.m. launch will go off on time and the crews can prepare their "quick-look reports" and get home before dawn.

Lt. Jim Guiterrez, the launch's countdown compliance officer, is seated next to Michaels. His voice is the most common one heard from the ILSC. At T-minus 58, his official launch countdown starts. "Prepare to initiate," he says in a ready-for-drive time radio voice. One by one, everyone checks in.

A moment later, off mic, he makes a fist and simulates rolling dice at a craps table. "C'mon baby," he says in his off-comms voice. "No holds!"

Sept. 21, 2013, 2:25 a.m.

35 minutes to launch

2nd Lt. Evan Fay, a 23-year-old key-turner with the 320th Missile Squadron, takes a moment to scan the clear sky before entering the launch control center. The pill-shaped capsule buried 70 feet underground is similar to the ones he mans in Wyoming, but more crowded. In the field there are only two missileers, but here there are four visiting airmen, plus two instructor/gurus called Top Handers (the ICBM equivalent to the Navy's Top Gun aviators) looking over their shoulders. The Glory Trip is a rare moment for missileers to be around other people who understand what consumes their lives. After all, these are people who obsess over a job that they hope they will never perform—except in simulated form here at Vandenburg. "There was a palpable feeling around what we were about to do," Fay would say later. "It would be something we could tell our children and grandchildren about."

Fay and 1st Lt. Philip Parenteau take hold of the keys at T-minus 30 minutes. There are waiting for a mandatory weather report and radar check. The word reaches the LCC—insert the keys and turn a triangular switch from SET to LAUNCH.

In the case of a real thermonuclear attack, a second pair of airmen in another location would at this point simultaneously turn their switches, and the ICBMs would be free. Here at Vandenberg, there is only one operational LCC at Vandenberg, but the missile is built to require a command from a second console. The solution: install a new console. The missileers start removing the 10 screws holding the console in place, with the clock ticking all the time. "It's a rush to swap the console," Rider says. "It's not a difficult procedure and we practice it in our simulators up north, and we also did it numerous times at Vandenberg in prep for the launch."

At T-minus 5 minutes, the countdown pauses for another mandatory check of the people and hardware, spread across half the globe. One by one, everyone reports systems are "go." In the ILSC, Michaels asks Kawane for permission to restart the countdown. It's given, and the range condition light switches from yellow to green.

Sept. 21, 2013, 3:00 a.m.

1 minute to launch

Rider and 1st Lt. Nathan Larson of the 321st Missile Squadron take their places at the newly installed console. Larson and Rider fix their eyes on the digital clock, hands on the switches. With 60 seconds left until launch, they simultaneously turn their hands and begin "terminal countdown." Seconds later the launch control center rumbles. Just a few hundred yards away, the ICBM is roaring to life in its silo.

Deep inside the silo, four ballistic gas generators blow the 110-ton silo door open. In the ILSC, the black and white video feed shows the silo door sliding away. It happens quicker than the camera's frame rate can handle, and the image skips like the lid of a vampire's coffin opening in a silent movie. The silo's exposed dark hole belches a white-hot jet of flame and smoke.

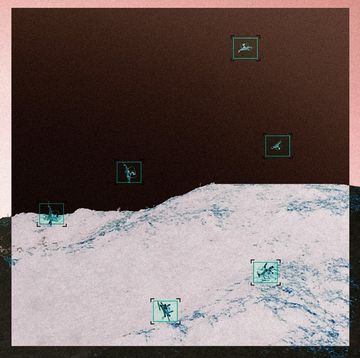

Three miles away, a group of missileers have gathered at the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Viewing Site, where a bust of the Gipper himself stares out to sea. Some of the airmen here are on call for emergencies. Others just want to watch.

The missile leaps from its hole, cutting through the plume and trailing a flickering lick of orange flame that illuminates the billowing smoke that obscures the projectile. The cheering from the viewing site starts with the first flash of light, before the first roar of 200,000 pounds of thrust reaches this hilltop perch.

Sept. 21, 2013, 3:01:01 a.m.

1 second after launch

Everyone at Vandenberg calls Mission Flight Control Officers by their acronym (MFCOs), pronounced "Miff-Coes." They have an unpopular job: to destroy the rocket if it veers off course. MFCOs are seen as existential threats to a rocket. Their motto—"Track 'Em or Crack 'Em!"—puts people on edge.

Call it the Misunderstood MFCO Blues.

Lt. Dylan Caudill, 23, is in the MFCO hot seat tonight. Caudill's screen displays a digital map with lines that the missile cannot cross. A GPS transmitter tracks the missile's location; an X marks the spot on Caudill's terminal. A elongated white oval extends in front of the X—this is the projected debris track in case the missile crashes.

If the Minuteman III crosses any safety lines on his map, Caudill will activate the switch that detonates explosives along the seam of the rocket. This is called "sending a function." It will not cause an explosion. Tather, it will crack the missile so the fuel rushes out before it ignites. The ICBM will then spiral harmlessly into the ocean—and the MFCO will have to answer for it. That's why the myth of a trigger-happy MFCO is just that. "I've never sent function to a vehicle," Caudill says. "I almost did, once. It was terrifying."

There's no more stressful time for Caudill than the first seconds of an ICBM flight, when he alone can determine the fate of a launch. There's no time to consult—a rocket can go off course within seconds and need to be destroyed immediately. In a process filled with shared responsibility, double-checks and redundancy, this is a time when an individual alone carried the weight of the operation.

This time, after a few seconds of vertical flight, the Minuteman III tilts and begins its journey west. Data about the missile's yaw, pitch and pressure readings stream into Caudill's console. "Because the Minuteman III pitches and rolls, sometimes even during a nominal launch, these screens can get spiky," he says. The High Accuracy Instrumentation Radar at Vandenberg follows the missile's progress as it continues its steep ascent. Caudill permits himself to relax a little. So far, the launch is picture perfect.

Sept. 21, 2013, 3:02 a.m.

1 minute after launch

An ICBM launch has the same flight profile as a basketball jump shot. There is an early, high-energy release, followed by an extended arc-shaped cruise, ending in a final plunge.

After a minute of flight, the Minuteman III is at an altitude of 100,000 feet, but just 18 nautical miles away. The airmen at the viewing site can clearly see the missile as a diminishing orb of light over the Pacific. Suddenly, the light splits. A second light blinks as it eases away from the first. This is first-stage separation. The spent tube falls away from the rising rocket and tumbles back to the Pacific. The missileers see this as a sign of a successful launch, and it is their last direct glimpse of GT 209. Unseen by those below, the missile's nose opens and exposes the three dummy warheads. Mini-thrusters on the missile's cone fire to steer the shroud away from the bulk of the rocket.

The Minuteman III is still rising, but also flattens its trajectory to head west. The second stage separates again at 126 seconds, when it is at 300,000 feet up and 120 nautical miles away. The second stage motor fires, producing 34,0000 pounds of thrust to project the missile higher. Tens of thousands of pounds of solid fuel combust in a single minute.

The once-towering rocket is now a stub, less than half the size of what left the ground. The third stage engine fires, but it's a short burn. At 180 seconds after launch, the third stage falls away. Only the section carrying the warheads, the post-boost stage ("bus"), remains as the missile reaches its astronomical apex and begins its descent.

Nuclear missiles often don't get credit for the fact they are advanced spacecraft. Consider that the International Space Station orbits at 260 miles above the planet, while the Space Shuttle flew between 190 miles to 330 miles above sea level. The Minuteman III's payload has a staggering maximum apogee of 750 miles. Anyone who says there are no weapons in space should see a launch like this one.

During the plunge back to the planet, the bus's liquid-fuel propulsion system rocket engine (PSRE) fires to adjust the trajectory of the warheads. Without a PSRE, a nuclear missile can only hit one target per missile. (The Minuteman III can carry a maximum of three warheads.) The system can also fire decoy warheads, confounding radar and defensive systems.

The PSRE fires its rockets to slow the spacecraft as it releases the warheads. A mechanism called a zero impulse bolt releases the warheads without changing their ballistic trajectory, leaving them locked on target.

Sept. 21, 2013, 11:28 p.m.

27 minutes after launch

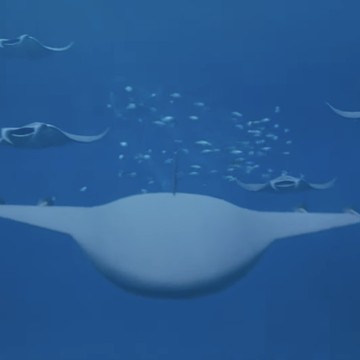

Out in the Pacific, the warheads appear as bright pinpricks—shooting stars following each other to the horizon. On Kwaj, radar in domes follow the warheads' progress. When the mock W87 warheads approach, batteries of high-definition, long-range cameras will capture their flight for analysis.

ICBMs are shooting at moving targets, as the launch code must contain an algorithm that takes into account the rotation of the Earth. To hit Moscow, for example, ICBMs aim at a point 186 miles east of the city. For such long range shots, and without guidance for most of the flight, ICBM warhead accuracy is impressive—the shot's circle error probability is reportedly as little as 500 feet.

At Vandenberg, all eyes are fixed on black and white screens showing the feed from Kwaj. A glowing dot appears and blooms into massive flare on the screen. The orb is followed by two others. When the warheads splash down, an underwater impact location system register their locations by the sound of their impact on the surface.

In the ILSC, the lights blooms and wink out of existence on the screens. The applause begins, high fives exchanged and headsets worn for hours put down on consoles. The room drains of personnel. Most of the civilians are heading home, but the airmen have to produce a "quick-look" report on the basics of the launch.

In the Pacific, the warheads settle to the bottom of the ocean, too deep for recovery. GT 209 is over. Everyone will take off the Cerberus patches from their uniforms.

Mutually assured destruction has again been confirmed. Most of the world continues to ignore the ICBMs dug into silos around the world. But the people in the business—the missile monkeys, the key turners, the Top Handers—continue to make them the centerpiece of their lives. They obsess over them so the rest of us can live happily, forgetting they exist and that Armageddon is still just a half-hour away.

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.