NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

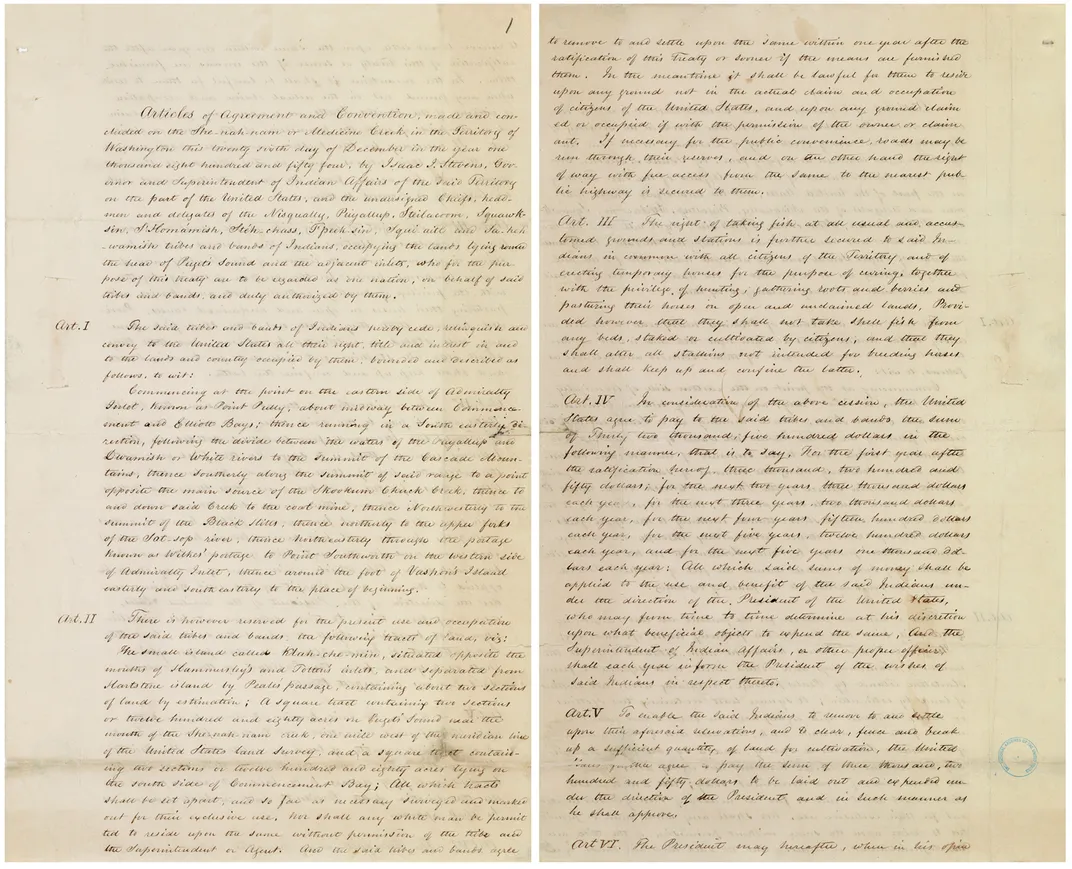

The Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854

Puget Sound Indians’ fundamental belief in the Medicine Creek Treaty helped inspire the great fish-ins on the salmon rivers of Western Washington in the 1960s and ’70s. Those acts of resistance fixed national attention on Indian treaty rights and laid the groundwork for the emergence of the modern tribal sovereignty movement that continues to define life in Indian Country today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Medicine_Creek_arrival_of_the_Walla_Walla.png)

On March 23, 2017, the Treaty of Medicine Creek (1854) was installed in the exhibition Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. The treaty, on loan from the National Archives and Records Administration, will remain on display through August 2017.

The words “broken” and “treaty” figure prominently in contemporary discussions on American Indian history. For good reason. Today, most historians agree that the United States violated many, if not all, of the roughly 371 treaties with Native nations ratified from 1778 to 1871. Yet the story of Indian treaties is more than a chronicle of coercion and bad faith. As the historian Alexandra Harmon reminds us, the narrative arc of treaty history makes “ironic twists and turns” and produces unexpected outcomes that have bolstered Native rights and tribal sovereignty.

The Treaty of Medicine Creek, with the Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin Island, and other tribes and bands of southern Puget Sound, was the first of four agreements the U.S. made with the Native peoples of Western Washington during a 37-day period in 1854–55. Although 63 tribal leaders signed the treaty, they and their people soon came to regret it. For in doing so they relinquished 2.5 million acres of tribal land to the U.S. in exchange for three 1,280-acre reservations, $32,500 paid over 13 years, and other considerations that aimed to assimilate Indians into European–American culture.

Flash forward to 1974. The descendants of the Medicine Creek Treaty signers embrace the old agreement. They consider it a source of Indian rights, a font of tribal traditions, and a recognition of sovereign nationhood.

What a difference 120 years make!

The shift in Native perceptions of the Medicine Creek Treaty turns on language found in Section 3, which states that, “The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory.”

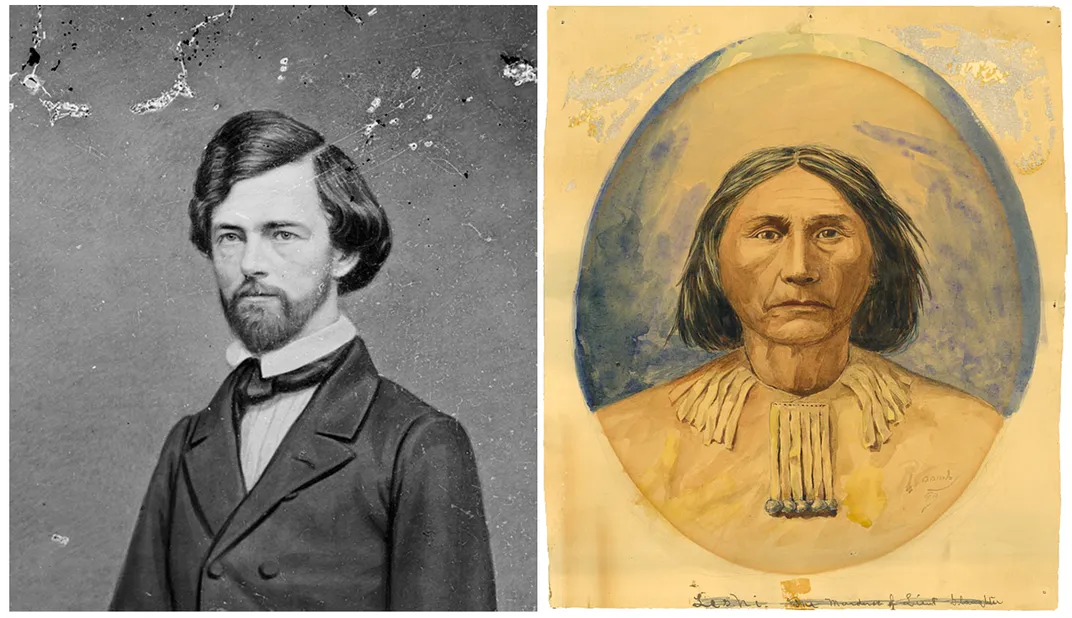

We tend to think that foresighted and hard-bargaining tribal leaders pressured American treaty commissioners to include such language in their treaty. After all, the Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin Island, and other southern Puget Sound tribes and bands depended on salmon fishing for survival. Yet the evidence suggests that the impetus for recognizing tribal fishing rights at Medicine Creek came from Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818–62), the lead U.S. treaty negotiator.

An ambitious graduate of West Point, the 36-year-old Stevens was the governor of Washington Territory—a vast and sprawling area that included northern Idaho and western Montana—as well as its superintendent of Indian Affairs. To him fell responsibility for negotiating land cession treaties with the Indians of the territory.

Acquiring legal title had become a matter of urgency in 1850, when the U.S. authorized white settlers to claim Native lands under a new homesteading act. Land cessions were needed to “extinguish” Indian claims to their homelands.

When he arrived at Medicine Creek, Stevens brought already-drafted treaty language that would be read to the approximately 600 to 700 tribal delegates who converged on the treaty ground on Christmas Eve 1854. The draft reflected a recent trend in U.S. Indian policy: Rather than removing tribes to far-flung lands, U.S. officials hoped to make treaties that consolidated Indians on small parcels, or reservations, within their original homelands.

Stevens’s treaty also reflected some understanding of the cultures of the Puget Sound Indians. He knew that salmon fishing was central to their lives, that tribal leaders would never countenance a treaty that removed them from their homelands’ streams, rivers, and saltwater bays. He also knew that U.S. Indian officials were stingy and that allowing Indians to fish on their former lands would reduce the government’s responsibility for feeding them. Last, Stevens knew that incoming white settlers would need access to Indian labor. For these reasons, Stevens’s treaty recognized Indian rights to leave their newly created reservations to work, hunt, and especially fish for salmon at their “usual and accustomed grounds and stations.”

The tribal delegates who attended the Medicine Creek Treaty expected to discuss and negotiate the terms of the agreement. But Stevens was not of a mind to negotiate. Ultimately the treaty was signed as written and forwarded to Washington, where it was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1855.

There is little doubt that the tribal leaders were confused by the proceedings. An interpreter read the terms of the treaty to them using the Chinook trade jargon, a 500-word pidgin language that had no words for Western concepts of land ownership, fishing rights, and other principles invoked in the treaty.

An X appears next to the name of the Nisqually tribal leader Leschi (1808–58), but there is reason to believe his mark may have been forged. Certainly Leschi was angered by the treaty’s plan to relocate the Nisqually to a small reservation atop a wooded bluff, away from the river where they traditionally harvested salmon. Leschi also visited neighboring tribes who were preparing to negotiate treaties with the U.S., urging them to place no faith in Stevens. As tribal resentment spread through the region, so, too, did white fears of Indian unrest. In 1855 the growing atmosphere of tension, distrust, and cultural misunderstanding led to violence and war. For eight months tribal warriors and volunteer militiamen engaged in skirmishes that cost lives on both sides.

In November 1856 territorial authorities captured Leschi, who was put on trial for allegedly killing an American soldier. Leschi’s attorneys not only proclaimed his innocence, but argued that an act committed during wartime could not be punished in civilian courts. The trial ended in a hung jury.

But Leschi’s troubles were not over. After a one-day retrial, a jury of non-Indians in a different venue found him guilty. Although his lawyers presented new, exculpatory evidence, the Territorial Supreme Court upheld the conviction. On February 19, 1858, 300 people gathered around an outdoor gallows near Fort Steilacoom, south of present day Tacoma, to witness his execution.

Leschi proclaimed his innocence to the end, and many people, including his hangman, believed him. “I felt then I was hanging an innocent man,” Charles Grainger recalled years later, “and I believe it yet.”

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the Native peoples of the Puget Sound region continued to remember Leschi as a great tribal leader and a wrongly convicted man. Today a neighborhood in Seattle, a city park, a marina, and a school on the Puyallup Indian Reservation bear his name. In 2004, 146 years after his execution, Leschi was exonerated at a historical retrial presided over by the chief justice of the Washington State Supreme Court.

In the 20th century, the Native peoples of Puget Sound also remembered and continued to invoke fishing rights guaranteed under the Medicine Creek Treaty. Exercising those rights, however, was now challenged by increasingly stringent state regulations that prohibited Indians from harvesting salmon out of season and without state fishing licenses. For state officials, U.S. treaties that guaranteed Indians the right to fish in their “usual and accustomed stations” were vestiges of a bygone era, ancient promises that held no purchase in modern America.

Puget Sound Indians never wavered in the belief that their treaty-recognized fishing rights were inviolate. “We have this treaty right, the supreme law of the land under their Constitution,” the Indian fishing rights advocate Valerie Bridges (Nisqually, 1950–70) declared. “It’s a treaty we’re fighting for.”

It was this fundamental belief in the sanctity and power of the Medicine Creek Treaty that helped inspire the great fish-in protests on the salmon rivers of Western Washington in the 1960s and ’70s. Those acts of resistance fixed national attention on Indian treaty rights and laid the groundwork for the emergence of the modern tribal sovereignty movement that continues to define life in Indian Country today.

Source for the observation that treaty history makes “ironic twists and turns”: Alexandra Harmon, “Indian Treaty History: A Subject for Agile Minds,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 106:3 (Fall, 2005): 358.