Adam Fontenot was visibly sauced. Having imbibed hard liquor for more than five hours without a bite to eat, Adam took on the role of a resident lush at the Up Stairs Lounge. He was, witnesses recall, able to giggle and nod in agreement with a speaker’s words but unable to participate more in the conversation. Nor did his compromised balance enable him to stand or move much from his bar stool. Buddy Rasmussen was busy, if also slightly annoyed with his lover. He was accustomed to seeing Adam in such a stupor, but he also felt partially responsible for serving him too many drinks this afternoon.

Buddy and his busboy, Rusty Quinton, had their hands full tending to the crowds, facing the ceaseless call for pitchers and mugs, and they soon forgot Adam. The beer bust was in full swing, with ninety or so patrons laughing and carousing on a carefree Sunday evening. Some patrons needed babysitting more than others. Plus, those not satisfied by bottomless beer were placing drink orders that needed to be filled. During hectic hours at the Up Stairs Lounge, one had to shout drink orders to Buddy, but they needed to be simple. Anything beyond a rum and Coke, a Bloody Mary, or a Cape Cod (vodka, cranberry juice, and lime juice) would be laughed off.

Nursing a drink, Steven Duplantis ran his eyes over the bodies around him, looking for a new squeeze. Prospects abounded, many in a condition that made them amenable to a pickup line. Steven tended to drink straight rum, as did many in the armed forces. Stewart and Alfred drank whatever and whenever the fancy struck them, but they usually sprang for vodka. Above their heads, a haze of cigarette smoke hung in bilious clouds that wafted just below the ceiling tiles. Window units pulsed with air conditioning, and Buddy tried to preserve the coolness by shouting “close the door” whenever patrons entered. Coins jangled in pockets or rolled across the bar, as many paid the beer bust fare in change.

Nursing a drink, Steven Duplantis ran his eyes over the bodies around him, looking for a new squeeze.

It felt like everyone was at the Lounge tonight. Robert Vanlangendonck, a newbie, kept his sunglasses on indoors. Perhaps he was closeted, people said, or maybe he was just so foggy from hours of drinking that he didn’t notice the shades on his face. Vanlangendonck’s friend Jim Hambrick, a toupee-wearing regular who looked more than a few decades Robert’s senior, had provided a ride to the French Quarter and was ordering drinks. Seeing a crowd form at the bar, Hugh Cooley agreed to pitch in a few hours early as a second busboy for Buddy. The MCC crew arrived in trickles: Deacon Courtney Craighead, around 5:00 p.m.; Deacon Mitch Mitchell with Horace after they’d dropped the kids off at the movies; and Pastor Bill Larson and the rest from the Fatted Calf. Witnesses recalled how they all looked primed for fun.

Ricky Everett, with out-of-towner Ronnie Rosenthal, snagged a table in the dance area so that they could talk with fewer interruptions. In an era when televisions had fewer than eight channels, bars were forums where people commonly struck up banter easily with strangers. “I just never could sit still in a bar,” explained Ricky. “I was too hyper. I would have a cocktail and, if I was not having a conversation, then I’d drift off to another bar.” Bartenders would often serve as conduits by making quick introductions. Ricky called Buddy Rasmussen a renowned “promoter” of dialogue, capable of juggling multiple exchanges and a telephone conversation at once. Buddy’s talents worked to Ricky’s advantage. Ricky’s mother, who lived across the river, was known to call the Up Stairs Lounge with messages. As a self-confessed “mama’s boy,” Ricky was still in and out of the family home as a tenant, and his mother insisted that Ricky give her a place to call when he was out, in case of emergencies. Despite all the shenanigans surrounding him in the bar, Buddy was known to play it cool when the phone rang. He kept people’s cover. One time when Ricky was out barhopping, Ricky felt a tug on the shoulder from a cute stranger — just over from the Lounge — who leaned in and whispered a message from Buddy Rasmussen: "Call your momma, Ricky."

Today, Ricky relaxed in a nook with Ronnie. Closer to the bar, Luther Boggs leaned on Jeanne Gosnell, his best friend and occasional beard — a female companion used as a ruse to conceal one’s homosexuality. They sat near the couple Reggie Adams and Regina and the inebriated Adam Fontenot. Perry Waters, the gay dentist, joked with a group. Was that sweet-voiced Francis Dufrene in from Harahan? Dufrene was known to catch two buses from the suburbs to reach the bar. He lived for these nights. And there was Willie Inez Warren, a gay mother “hen,” and her two “gay for pay” sons, the part-time hustlers Eddie and James; they were considered shabby but honest folk, always off duty at the beer bust.

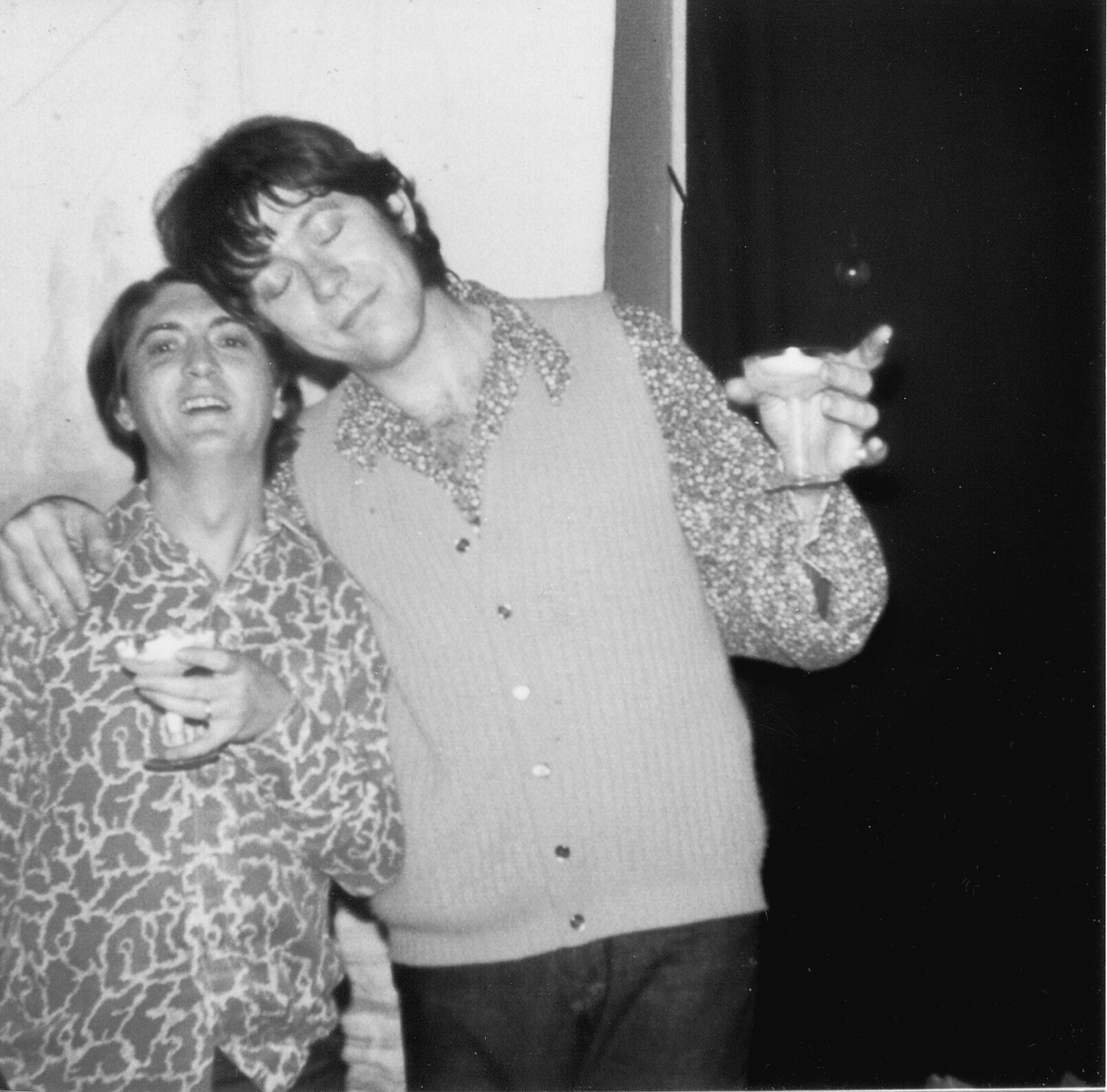

Worlds inevitably intermixed. Stewart Butler chatted with Horace Broussard, Mitch Mitchell’s lover and Stewart’s regular barber. “That’s where I’d make a barber appointment,” recalled Stewart. “I’d just made an appointment with him that night.” Jason Guidry, sometimes called the “bar dingbat,” was present as well (Guidry was a very common surname in Louisiana, and Jason was no relation to the hustler Mark Allen Guidry). The place seemed to darken a bit toward the grand piano in the corner, which was lit up to provide a stage for performers. Some of the windows on the Chartres Street side were shuttered to accentuate the feeling of privacy. Patrons like John Golding, who’d recently celebrated twenty-five years of marriage to his wife, appreciated these precautions.

John had much to lose by drinking at the beer bust. He was a prototypical blue-collar breadwinner, working as a salesman at a cigar shop and living with his family near the Lower Garden District. For decades, John and his wife, Jane, had had an understanding. She didn’t venture with him downtown, and he didn’t let his fun creep back into their marriage. “She clearly accepted Dad for who he was,” explained their son, John Golding Jr., who was eleven years old in 1973. “Yes, there was this void of homosexuality linked to Dad. That was always there, but Mom was accepting of it and clearly very attached to him. They shared a bed. It wasn’t just a black-and-white, ‘it-was-all-deception’ dynamic.”

Although their arrangement was loving, it wasn’t ideal. Months before, John had been fired from his well-paying job at a public utility after being caught in a homosexual act. This wasn’t his first such incident, but luckily this one stayed out of the newspaper and didn’t become neighborhood gossip. That night in June, Jane had served her husband spaghetti as part of their family’s Sunday ritual. Before he walked out the door for the evening, they kissed goodbye. They had three children together, but two were already out of the house. With John off to do whatever he did, Jane readied John Jr., their youngest, for sleep. Now John Golding mingled at the beer bust with Dr. Waters and other men, whom John called “lovers” but Jane thought of as her husband’s “friends.”

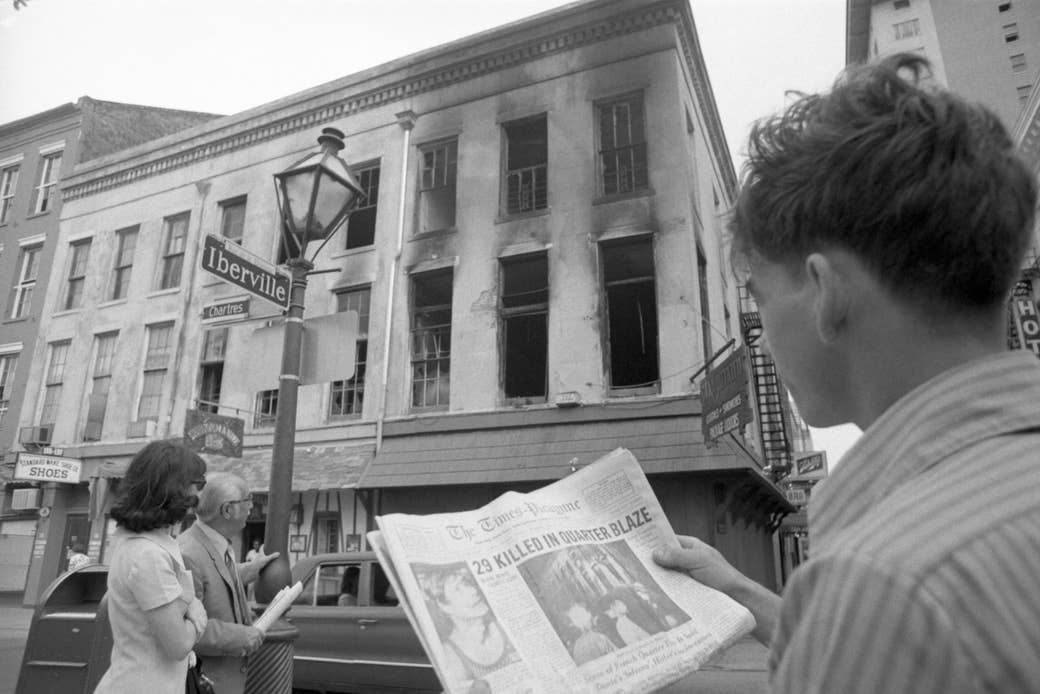

These patrons wished, beyond all else, to avoid public declarations of their lifestyle. Individuals caught by the police and charged with offenses would be outed when their names were routinely published in the “Orleans Parish Records of the Day,” a popular section of the Times-Picayune. In this police record, names would be listed beside alleged crimes and alleged attempted crimes — indeed, according to Louisiana’s criminal code, an attempted crime against nature could be prosecuted. A gay man didn’t actually need to commit a homosexual offense to face a penalty; conspiracy, or intent to commit, could be sufficient, if proven. The state’s sodomy law, ostensibly on the books to prosecute any type of nonmarital sex from adultery to bestiality, was most often employed to prosecute same-gender sex and at one time prescribed a mandatory penalty of life imprisonment with hard labor for a single offense. By 1973, the charge had been reduced to a felony with a minimum two-year prison sentence. And, even in the event that a charge was dropped due to lack of evidence, a name would often still appear printed in the newspaper beside the annotation “nol prossed,” meaning not prosecuted. “That pretty much ended your life in New Orleans,” recalled John Meyers, the gay seminarian who lived near the Up Stairs Lounge.

These were the stakes, pressing in from the outside world. But all seemed different inside the Lounge, as if freedom reigned to the tune of David Stuart Gary’s piano. Piano Dave was tearing it up to the delight of partygoers. A crowd gathered as melodies poured forth. The twenty-two-year-old performer paid his rent through the tip jar, posted on the bench, as well as through a steady gig across the street at the Marriott. He took some gigs for the money and others for the soul — the Up Stairs Lounge was clearly such a soul gig. Dave grooved on his instrument. Notes reverberated into the dance area, where Ricky and Ronnie laughed and boogied. A gay pied piper, Piano Dave played, and New Orleans’s gay working class turned out in force. Rooms overflowed, though the Lounge always seemed to keep within its fire code capacity of 110 people.

Rooms overflowed, though the Lounge always seemed to keep within its fire code capacity of 110 people.

Circulating closer to the piano was George “Bud” Matyi, a semi-famous musician who performed under the name “Buddy Stevens” and appeared with the house band on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Bud Matyi was what was considered an “A-gay,” a sophisticate who owned a condo near the lakefront. Bud’s lover, folks whispered, was Rod Wagener, an afternoon talk show host on radio stations WDSU and WGSO. Given their public personae, Bud and Rod were forced to hide their relationship from fans. Most who knew them understood that public exposure of their lifestyles would destroy their careers. Nevertheless, Rod and Bud lived in conspicuous luxury. They drove a 1966 Chevrolet Camaro convertible, a “muscle car” that turned heads. According to a blurb in Billboard magazine, Bud Matyi had just signed a management and recording deal. Not unlike Clay Shaw before his downfall, Bud was a man on the verge of celebrity, a person with something to lose.

As Rod steered their convertible down Iberville to drop off Bud at the Up Stairs Lounge, he couldn’t hide his agitation with Bud’s desire to visit such a dingy block. Of course, there were personal complications. Despite being only twenty-seven, Bud Matyi had three young kids — Tina, Todd, and Shawn — back in California from two previous marriages. Bud had, in fact, parted ways with his second wife, Pamela Cutler, when he met the handsome Rod Wagener. “She said my dad left her for a guy,” Tina Marie Matyi recalled her mother telling her. “And I feel that she felt betrayed in that aspect of it.” As an innocent lie to help the children, Pamela Cutler explained that Rod Wagener was now important to their father because he was a “business manager.” Bud Matyi filed for preliminary divorce in 1972, but the proceedings were still pending. Emotions stayed raw as Bud and Rod attempted to negotiate some form of custody arrangement with Pamela. All the while, Rod formed emotional attachments on the phone with Bud’s kids. “I was told by my grandmother that Rod and my dad were going to come and get us,” recalled Tina Marie. “And they were going to take us and fight for custody for us. And they were going to raise us.” This impossible dream of a gay family made whole, with gay lovers at the helm, seemed tantalizingly within reach.

But Bud had promised that he’d pitch in on the piano that night. Unable to dissuade his lover, Rod had slowed to a stop beneath the Up Stairs canopy. They kissed before Bud hopped out. A medal of a dove clutched by two hands, the Catholic symbol of the Holy Spirit, swung around Bud’s neck as he climbed the stairs.

Polyester, that mainstay of 1970s fashions, clung to male bodies as patrons sized one another up and likely chatted about such topics as Secretariat’s recent Triple Crown triumph; Deliverance, a hit movie from the previous year starring the hirsute Burt Reynolds (whose arousing poster in the bar made “purty mouth” jokes a go-to); or whatever cantankerous jibe Archie Bunker, a beloved if also bigoted character, had gotten away with on All in the Family, the top-rated series of the season. Maybe they chatted about the movie being filmed down the street, My Name Is Nobody. Or about effete television personalities like Paul Lynde on Hollywood Squares or Charles Nelson Reilly on Match Game, game-show contestants whose double entendre–laden wisecracks helped them play the “nancy,” a vaudeville-era term for an effeminate male jester. Nancies were, in fact, caricatures that society had been trained to laugh at: fey, limp-wristed, speaking with a lisp, with no social defense but a quip. Lynde, particularly, had perfected his shtick and made it family friendly enough for the sitcom Bewitched. Even though Lynde’s sexuality might have seemed obvious, especially in retrospect, many of his fans lacked the context in his heyday to question whether he was actually gay. There were few other gay icons to chat about. David Bowie’s audacious claims of bisexuality, recently said while wearing epicene attire, were more the mechanisms of courting controversy than candid affirmations of difference. In the literary world, Gore Vidal and Truman Capote both walked a clever line and played off their affectations as the eccentricities of brilliant minds.

Roger Dale Nunez stumbled through the door of the Up Stairs Lounge and into the beer bust. Through his forays in and around Iberville, Roger had visited the Up Stairs Lounge on several occasions, although the regular patrons, nonjudgmental as they were, hadn’t exactly welcomed him. Roger, who was more of an outsider in a jovial society of buddies, functioned better in the hustler bars, where men went alone. Although many on Iberville had seen his face, few had taken the trouble to learn his name. Ricky Everett vaguely remembered seeing Roger at the Lounge, but it’s telling that even kind-hearted Ricky didn’t consider Roger a friend.

Roger looked rough and drunk enough that night to be a hassle. Steven Duplantis remembered hearing an audible reaction to the guy’s presence, as if people were saying, “He’s here again?” Behind Roger walked Mark Allen Guidry, the younger hustler. Ignoring the wisecracks, Roger headed straight for the bathroom before he could be served, which left Mark Allen Guidry standing alone. Mark must have felt stranded, socially speaking, after the less than enthusiastic reception, and he didn’t stick around long. Roger didn’t seem to notice. He stationed himself in one of the two men’s room stalls and began gawking through a peephole at patrons using adjoining facilities.

Close to the altercation, Steven Duplantis heard Roger say, "I'm going to burn this place to the ground."

According to those present, Roger whispered comments of encouragement or harassment to those in the neighboring stall, perhaps hoping to win a friend or torment a quick lay from someone with a fragile ego. But his tactic created a bottleneck. The line to the bathroom soon backed up past the bar, and patrons began to get testy. Buddy seemed preoccupied. An eighteen-year-old named David Dubose, a youngster not in the bar’s employ, was gathering empty beer mugs and attempting to return them en masse. Dubose wanted to claim the fifty-cent deposit on the mugs and use the proceeds to further imbibe. But Buddy and Hugh caught him in the act and refused the extra coinage. In retaliation, Dubose began “pouring beer on the floor, kicking the customers, and being loud.” It was teenage revenge.

After a raucous but hardly uncommon afternoon-into-evening session, the beer bust ended at 7:00 p.m., and people stood and sang “United We Stand.” Beer pitchers returned to ordinary prices, and half of the crowd had departed as Dubose headed for the bathroom. He cut in line, to the chagrin of other patrons like Robert Vanlangendonck, who had been waiting his turn. Dubose began pounding on the occupied stall door, the one holding Roger Nunez. He repeatedly cursed at whoever was inside and refused to come out, but then he noticed Steven Duplantis standing at the sink.

Dubose grabbed at Steven and proposed a blowjob for five or ten dollars. Although they were around the same age, Steven was unimpressed. Steven rebuffed him with a “No, you’re just trash,” but Dubose failed to take the hint. “He wouldn’t leave,” remembered Steven. “So he stayed in the bathroom. I went straight and told Buddy.” Hustling was a rule violation, and Steven’s report would mean immediate ejection. However, just as Steven blabbed, Michael Scarborough entered the empty bathroom stall and heard Roger Nunez’s whispers.

Evidently, Roger said the wrong thing to Scarborough, a man who had grown up tough. Michael’s father was one of the biggest bail bondsmen in the city, a strongman who made employees call him “sir.” Having learned to stand up to that domineering figure, Michael wouldn’t just accept the taunts of a drunken stranger. Enraged at the Peeping Tom, Michael left the bathroom and reported the conduct. Buddy Rasmussen weighed whether to act first on the Peeping Tom gumming up the bathroom or the hustler pouring beer, and decided to start by clearing Roger out. Buddy and Hugh Cooley entered the bathroom, pulled Roger Nunez from the stall, and told him to leave people alone.

Suspicious of a snitch, Roger began looking for Michael Scarborough. Spotting Michael by the piano, the highly inebriated Roger ran at him. Michael was sitting at a table with his lover, MCC patron Glenn Green. Born on All Saints Day, Glenn was a gentle soul and the steadier of the two lovers. He had grown up in Michigan with two macho older brothers serving in the army. Glenn himself enlisted in the navy. He’d been stationed in Okinawa and spent three years in the service of a high-ranking admiral. But, according to Glenn’s sister, Naoma McCrae, he was caught having sex with another man and discharged for “medical reasons.” Now in New Orleans, Glenn worked as a clerk at the International Trade Mart. On his off days, he helped elderly neighbors.

Glenn Green likely tried to ignore Roger. Michael, however, would let no one insult him. So when Roger shouted a few epithets, Michael stood up and leveled Roger with a punch to the face. “He came over and started agitating me,” Michael said later, “so I jumped up and just knocked him down.” Roger fell to the floor and, groaning in pain, stayed on his back for a minute, until Buddy and Hugh gathered him up. Now Buddy had another decision to make: eject Michael for fighting Roger, or eject Roger for inciting the fight. Since Michael was popular at the bar and Roger was too intoxicated to be served anyhow, Buddy moved to eject the injured man, who would probably bother more patrons if they let him stick around. Before he could stand up on his own, Roger yelled something Michael heard as “I’m going to burn you all out.” Close to the altercation, Steven Duplantis heard Roger say, “I’m going to burn this place to the ground.” It’s worth underscoring that, even above the teeming noise of the bar, both men heard the word “burn.” Buddy and Hugh proceeded to drag Roger toward the bar entrance as Roger kicked and spat. “It took two or three people to get him to the upstairs door,” recalled Steven. “There was an altercation to get him out,” Steven continued, “even out on the landing.”

The violent scene shook Steven out of his reverie. He checked his watch and realized it was time to leave. He knew he had to go right then to reach San Antonio by sunrise. He’d be driving at top speed through the night to make it back to base, but something about that guy screaming “burn” felt wrong. “Especially the way that he said it,” Steven remembered. He turned to Stewart and Alfred and told them, “Y’all need to leave here,” to clear out and head elsewhere. “Stewart was having fun and hearing none of it,” Steven continued. Alfred took Steven’s side immediately, but Alfred suffered from frequent bouts of paranoia that made Stewart roll his eyes. “Alfred says, ‘I want to leave,’ ” recalled Stewart. Steven tried to persuade Stewart further, but he couldn’t wait any longer. Having passed the message, Steven kissed his friends and took off. With Steven gone, Stewart tried to dismiss any notion of leaving, but Alfred persisted until Stewart had to listen.

Meanwhile, Buddy and Hugh dragged Roger down the staircase and out the front door by his shoulders. They returned to find David Dubose, the teenager, as defiant as ever, dancing with two beer mugs that he hadn’t paid for. Having hustled and attempted to steal, Dubose was clearly not welcome anymore. They dragged him, mugs in hands, down the front stairs. Buddy told Dubose to “leave and never return” and tossed him onto Iberville Street. Realizing that he was still holding the mugs, Dubose threw them at Buddy in a rage. They shattered in the bar’s entryway, littering the inside foyer with glass.

Dubose stumbled away, and Buddy asked Hugh to sweep the entrance while he went back upstairs to man the bar. Perhaps sensing an opportunity in an out-of-control teen, an older man named James Smith left the Lounge and caught up with Dubose. Smith proposed a sexual fling, and Dubose accepted. They staggered back to his apartment, where Smith cooked Dubose a meal and then gave him a blowjob for ten dollars. Eventually, Smith drove Dubose to the Golden Slipper Lounge on the northern edge of the Quarter.

Back upstairs, the Nunez altercation and Dubose’s ejection had certainly caught the attention of patrons and become fodder for conversation, but the ruckus in no way ruined the evening. No one would mistake the Up Stairs Lounge for a high-toned establishment, and Buddy and Hugh had handled things quickly and efficiently. “The fight was over just like that,” recalled Buddy. Still, Mitch and Horace must have been glad that they dropped off the kids. They tended to think of the Lounge as a family place and, the previous year, had held their holy union ceremony and reception in the bar area. As such, they sometimes brought Duane and Stephen along on beer bust night, but this evening’s violence would have been confusing for children to witness.

Down the street, at the Walgreens on the corner of Iberville and Royal, a white man in his midtwenties walked through the doors. He had dark brown hair, a ruddy complexion, and a medium build. Standing behind the register, cashier Claudine Rigaud made a practice of greeting her regular customers by name, but she’d never seen this man. He walked directly to the counter and asked to buy a can of lighter fluid. He appeared to be heavily intoxicated. Rigaud showed him where the fluid was kept and noted the sizes available. Ronsonol, the iconic lighter fluid in a yellow can with blue letters, had long been sold at French Quarter drugstores. It’s a petroleum distillate commonly used as fuel for Zippo-style lighters.

Rigaud thought nothing of the man’s request. This store did a good bit of business in tobacco products, in this era when smokers could light up almost anywhere. But something else did pique Rigaud’s attention: the man’s hands were visibly shaking, and he seemed to be, in her words, “emotionally upset.” No stranger to Iberville Street culture, Rigaud assessed that this man—soft-spoken and “feminish”—might be gay. Nevertheless, a customer was a customer, and Rigaud was about twenty minutes from her evening break. Apprised of the can sizes, seven and twelve ounces, the man asked Rigaud if a smaller can was for sale, but she informed him that the smallest and cheapest of cans, four ounces of Ronsonol, had recently sold out. So the customer reluctantly purchased the medium-size can and left.

Meanwhile, aggravated to be departing from the bar so soon, Stewart tramped down the staircase with Alfred, whom Stewart thought must be experiencing another emotional episode. They halted at the landing and shouted in a couple’s row very likely witnessed by William White and Gary Williams—two teens poking their way around wild French Quarter bars. White and Williams, jittery youths, bolted as Stewart and Alfred took their argument down the stairs. Trailing them all was Regina, born Richard Soleto. She and Reggie had dinner plans with Buddy and Adam, but they needed money. Reggie offered to run back to their apartment, but Regina insisted that she do so. They pecked, and she left.

At the bar, Buddy counted out his register and prepared to formally hand over duties to Hugh Cooley at 8:00 p.m. The night had been wild, and Buddy just needed to go to the storeroom, secure his money in the safe, and call it a day. By the Chartres Street wall, Piano Dave was chatting up patrons, perhaps speaking with a few frequent tippers who had taken a liking to him, and Bud Matyi played exuberantly at the bench. A few of the drag queens scheduled to perform for the charity benefit for the Crippled Children’s Hospital had yet to arrive, but time was loose on beer bust night.32 Matyi’s hands danced across ebony and ivory. Hammers hit piano wires as, down below the Up Stairs Lounge, someone stood at the base of the stairs. This person — very likely the Walgreens customer but unwitnessed in the act — proceeded to empty seven ounces of lighter fluid from a yellow Ronsonol can onto the left side of the second step and then drop the canister. The porous wood of the staircase, more than a hundred years old, drank the fluid effortlessly. The red carpeting, running like a ribbon over lumber, sopped up the rest. On the second step, a patch of wet carpet sat ready like a wick. Searching pockets for a lighter or match, the assailant then dropped two ten-dollar bills, which floated down unnoticed. A spark was lit. Then the unmistakable smell of smoke. ●

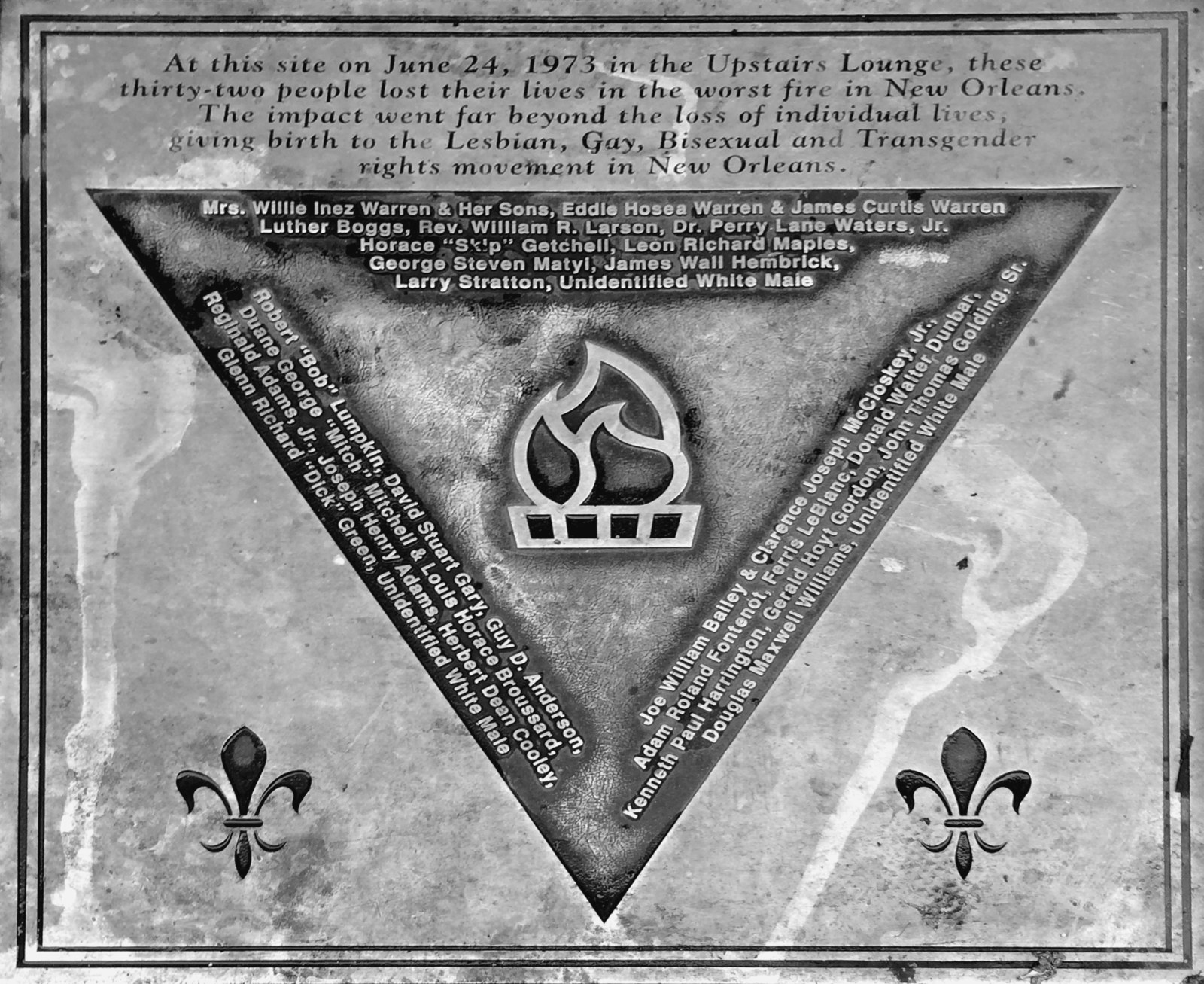

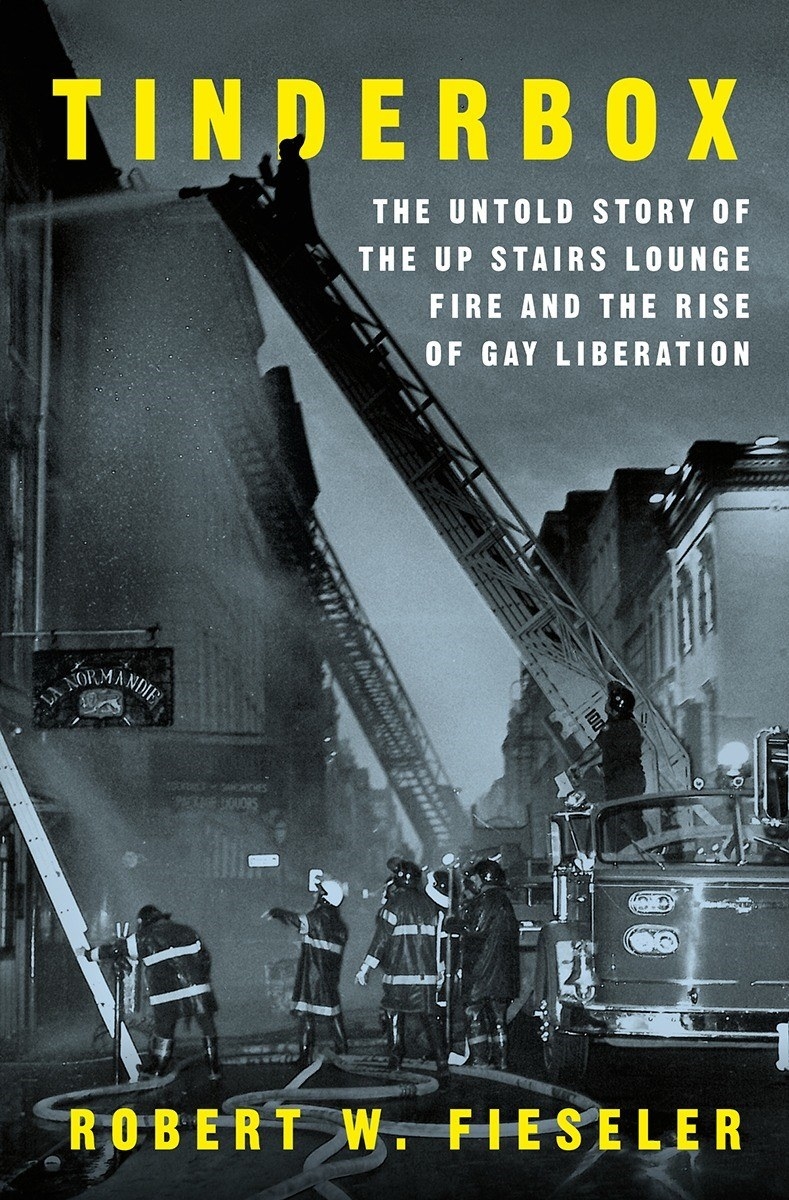

Excerpted from TINDERBOX: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation by Robert W. Fieseler. © 2018 by Robert W. Fieseler. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Robert W. Fieseler is a journalist and a recipient of the Lynton Fellowship in Book Writing and the Pulitzer Traveling Fellowship. He lives in Boston.